Welcome to Today’s!

good day!

bonjour!

dzień dobry!

добрий день!

zdravstvujtye!

ŋkekea me nenyo!

mwaramutse!

maidin mhaith

bom dia

buen día!

guten tag!

dobrý den!

اچھا دن

İyi günler

kαλημέρα

goedemorgen

ብሩኽ መዓልቲ

yá’át’ééh

god dag

magandang umaga po

สวัสดีตอนเช้า

Indeed, it is a good day and it will be a good day. Tomorrow will be even better but we must focus on today as:

“the only time that is important is NOW. It is the most important time because it is the only time that we have any power”

Leo Tolstoy

We have the power TO BE today before we meet tomorrow.

“Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we might fear less”.

Maria Curie-Skłodowska

If you have already subscribed, it means that you already helped me to understand more so I will want to share with you what I see and how I see it: simple monologues I have with myself when you don’t hear me, some reserved reflections... We might not have time or words to say it all in person so write to me if you wish. I am interested in what you think.

If you have already subscribed, it means that there is an exclamation mark next to the ‘good day’ in your language.

If you haven’t subscribed yet, let me know your perspective on today or tomorrow and we might meet somewhere halfway through!

Subscribe to get full access to the newsletter and publication archives. If your language is not at the top of this page, let me know and I will be happy to learn how to pronounce ‘good day’ your way!

Why is then ‘good day’ written in lower cases? As for tomorrow to become capitalised, we need to first make today happen and we do it by small, individualised efforts, one by one, one for one.

HAVE A GOOD DAY AND MEET ME THE NEXT TIME!

For more patient readers:

All is One

Wholeness is real; fragmentation is a human mechanism that needs dismantling to allow the flow

Who won’t admit that the first encounter with physicists is rather theoretical and brief, consisting precisely of a few lessons in high school, uniquely in Science. Something similar could be said of Far East philosophy. Almost no one thinks of spirituality when discussing Science. Until someone does.

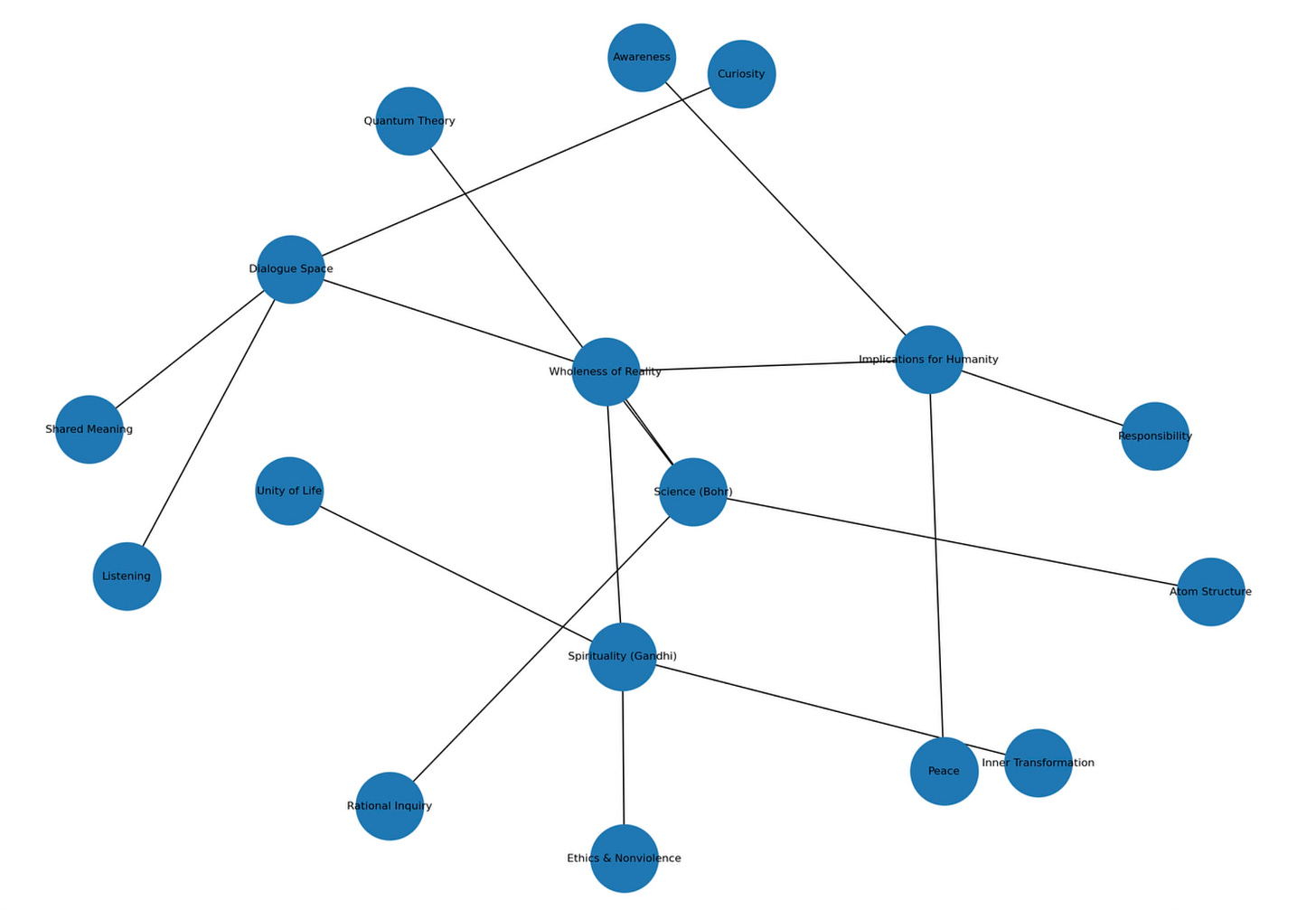

David Bohm (1917–1992) was a theoretical physicist, most known for his theory of the implicate and explicate order. In his later life, he developed a philosophy of dialogue which grew out of his observation that fragmentation is one of the reasons for the many crises we face as a global society. Our societies, organisations and even ourselves are fragmented; we have lost sight of the whole and that all livings things are interconnected, interdependent and interrelated. This is why Bohm recognised that what we so desperately need is new thinking, and that we struggle to arrive at this new thinking because we do not create the time and space to come together and meet in a meaningful way or create the conditions in which we can allow new thinking, and thus change, to occur.

He, a friend of the Dalai Lama, was a change-maker who, among others, got closer to the intuitions of our ancestors, especially those living in the Far East. The teachings of Hinduism, Taoism, and Buddhism reveal truths that correspond to the descriptions of quantum physics.

From Buddha to Bohr

Contemporary physics outlines a picture of reality in which all components of matter and physical phenomena depend on one another and are interconnected in various ways. Looking at the structure of the atom, we notice that it is composed, among other things, of electrons that move in spaces around the nucleus.

What an electron is constitutes a true challenge for our minds because it has two — seemingly — contradictory natures: it is a wave and a piece of matter.

In fact, even these concepts do not fully capture its essence, especially since its “behaviour” depends primarily on the situation. In other words, an electron does not exhibit any properties that would be independent of its environment. It is therefore not a “thing” in our usual understanding of that word. Rather, it enters into relations with other particles, weaving with them a complex network of dependencies, ultimately creating the entire material reality.

Niels Bohr (1885–1962), a Danish physicist and Nobel laureate, expressed this in his book Atomic Theory and the Description of Nature in the following words:

“Isolated material particles are abstractions, and their properties can be defined and observed only through their interactions with other systems.”

Werner Heisenberg, a German theoretical physicist and philosopher of science, speaks in a similar tone:

“The world thus appears to us as a complicated tissue of events, in which various connections alternate or overlap or combine and thereby determine the texture of the whole.”

This relational model is at the same time one of the basic assumptions of Buddhist doctrine: the nature of reality is the interdependence of all phenomena and elements. Nothing can exist independently of everything else. This principle in Buddhism is defined by the term śūnyatā. It is most often translated as “emptiness,” which is rather unfortunate, because our understanding of emptiness is based on the lack of something. Here, however, it is not about lack, but rather about non-substantiality, which at the same time is absolute potentiality — the possibility of the emergence of anything, any phenomenon or form.

Looking at a chair, we say: “chair.” But it is not a chair. We only call it a chair. In the chair there is nothing of “chair-ness,” that is, an internal characteristic that would determine that it is a chair. Its nature is empty, which means that it is conditioned by everything else (that which is not the chair), while in turn conditioning the entire reality.

It is similar with our self, which we treat as a real and separate entity from the world. However, from a Buddhist perspective, this reality is a universal illusion, and our true nature is empty — that is, conditioned by everything that is seemingly not us: our ancestors, other people (even strangers), the elements, or non-human beings.

The illusion of separation

In everyday life, we perceive the world in terms of the separation of various objects from each other, and we cultivate our own sense of independence. Yet both modern physics and the wisdom of the Far East challenge this independence — it is a universal illusion.

Hindus call it māyā — the illusion that accompanies us every day when we are preoccupied with the matters of life. Māyā causes us to identify with our small self and look at the world as if it were composed of other isolated elements. In this way, we see ourselves and our surroundings detached from the common Source. A manifestation of this is, for example, identifying with the material body (ahaṃkāra), as well as attachment to possessed things (mameti). Meanwhile, the goal is to break the shackles of illusion and unite with Brahman — the impersonal absolute that is everything that exists. In the Bhagavad Gita we read how Krishna, who is a form of Brahman, speaks to Arjuna:

“Earth, water, fire, air, space, mind, reason, and the sense of individual self — thus is divided My eightfold nature. This is My lower nature. But know My higher nature too! It is the principle of life, O Hero! It sustains this world! Know that from both of these all creatures arise. I am the source of the entire world and its destruction […]. I am the taste of water, O son of Kunti, I am the brilliance of the moon and the sun, the sacred syllable in all the Vedas, the sound in space, the valour of warriors. And the pure fragrance of the earth, and the glow of fire, the life of every creature and the heat of the passionate.”

Nāgārjuna, the 2nd-century founder of the Buddhist philosophy of Madhyamaka (the Middle Way), also shared the view of the illusory nature of our daily perception. For the truth is that nothing has an independent existence. Realising unity is therefore liberation from illusion, an awakening from a nightmarish dream.

Modern physics emphasises that matter is only a manifestation of energy, which, as a quantum field, constitutes the basic physical whole, the constant medium present throughout all space. Particles (forms), on the other hand, are local condensations of the field, concentrations of energy that appear and disappear, thus losing their individual character.

In one of the most important Buddhist texts, the Heart Sutra, we read:

“Form is not different from emptiness, emptiness is not different from form; form is exactly emptiness, emptiness exactly form.”

In the language of modern physics, this might sound as follows: matter (impermanent forms) does not differ from energy (the field that permeates, creates and connects everything).

It is not easy to understand, because according to our mind, the idea of interdependence and emptiness does not match everyday experience in which we divide reality into separate chunks, attributing to them inherent properties.

Quantum physics and the wisdom of the Far East pose many challenges to our discursive reasoning. Another one is the idea of the unity of opposites.

Opposites are the same

Modern physics indicates that everything has its other side. Fritjof Capra recalls the fact that each particle has an antiparticle with the same mass but opposite electric charge. And so the antiparticle of an electron is a positron; there also exist the antiproton, antineutron, and antineutrino. Even the photon has its antiparticle, although it itself lacks electric charge. The same applies to mesons.

We already know that all matter has a dual nature: it manifests as particles and waves. Their behaviour is difficult to predict — we can do so only by using the concept of probability. There is no certainty that an atomic particle exists in a specific place. Robert Oppenheimer — an American physicist, creator of the atomic bomb — described this paradox as follows:

“If we ask, for instance, whether the position of the electron remains the same, we must answer ‘no’; if we ask whether the position of the electron changes with time, we must answer ‘no’; if we ask whether the electron is at rest, we must answer ‘no’; if we ask whether it is in motion, we must answer ‘no’.” In the roughly 2,500-year-old Upanishads, we read: “It moves and it moves not. It is far, and it is near. It is inside everything, and it is outside everything.”

Is that not a striking coincidence?

We say: beautiful—ugly, good — evil, life — death. These individual categories are connected with human experience of various physical and emotional sensations. Hence our tendency to separate pairs of opposites and to eliminate the part of them that is responsible for suffering. We want life and do not want death; light is good, while darkness evokes anxiety. Here, we can notice how the isolated, frightened self tries to separate certain phenomena from others to feel better and protect itself from difficult experiences.

By realising unity, we make our perception and understanding of seemingly separate phenomena change. What was previously separate again becomes an inseparable whole.

Touching the paradox

This also has consequences for logic, for it turns out that truth includes its own negation. In this way we see how reality resists the possibility of being described, known, and understood by discursive language and a mind accustomed to divisions. Quantum physics reveals to us many such paradoxical truths: matter, which is a form of energy; the vacuum from which everything that exists arises; electrons which are neither particles nor waves; time which is relative… The wisdom of the Far East also contains many similar paradoxes that cannot be understood at the discursive level of the mind. The schools of Zen Buddhism have even made the formulation of such paradoxes into a kind of practice through which the student can experience the one reality and awaken. They are called koans and constitute a true challenge for our intellect.

An example of such a koan is the question: “What was your original face before your mother and father were born?” The “original face” here is a synonym for our true nature. Our self, with which we identify and which has its beginning in the story of our life, is something else. That life appeared through our parents. But who were we before their birth? What did our face look like then? Who are we really if we put aside our everyday identity? All these questions seem meaningless from a common-sense point of view. After all, our life began with birth. We could not have had any face before our parents were born. These contradictions dissolve, however, if we transcend thinking in terms of a separate self and refer to the idea of interdependence and the unity of everything.

Taoism is also full of such paradoxes. Laozi in the Tao Te Ching writes: “Pure whiteness is not without flaw; to possess great Power is not everything; established Power hides indolence; the strongest change their minds; the greatest square has no corners; the greatest vessel has no formed shape; the loudest sound is inaudible; the greatest Image is formless. Tao is hidden and without a name. Without leaving home, one may know the world. Without looking out the window, one may see the greatness of Tao. The further you go, the less you know. Therefore, sages do not travel, yet they know everything. They do not see, yet everything is clear to them. They do nothing, yet everything happens by itself.”

The discovery of the unity of opposites does not mean denying that two poles exist. It is about realising that both ultimately become one. As in the case of breathing, in which inhalation and exhalation are opposing processes, although breathing creates a coherent whole out of them.

Everything is in motion

The process of breathing, like every other, is inscribed in a cycle of transformations. This is another important characteristic of how reality functions, revealed to us by modern physics and once again confirmed in the wisdom of the Far East. Every day we encounter objects that seem hard, motionless and durable, such as rocks or stones. However, these are just appearances, because when we go inside such a “dead” object, we see that it vibrates with energy. Both atoms and the bonds between particles are in constant motion. This movement is associated, among other things, with thermal energy that flows between an object and its surroundings.

Cyclical transformations can be observed in everyday life and on an even larger — cosmic — scale. Motion, which is the fundamental principle of reality, is inscribed in two opposing yet interconnected processes: creation and destruction. In the spiritual traditions of the Far East, the dynamics of transformation and the impermanence of forms are also described as the essence of reality. And so in Taoism, tao means a process embracing everything. Its essence lies in transformations based on the balancing of the elements yin and yang, that is, feminine and masculine energy. Nothing is permanent and unchanging, except for tao itself, whose nature and origin are a great ineffable mystery.

A similar thought can be found in the Hindu metaphysics of Sāṃkhya, which is based on a dynamic balance between the aspects of spirit and matter. In Buddhism, the idea of the impermanence of everything is the foundation of the First Noble Truth, which says that suffering is universal. Everything passes away, which inevitably involves the experience of loss, and that brings suffering. Therefore, we long for permanence, but this only intensifies suffering because it opposes the fundamental rule of reality. Accepting impermanence — that is, giving up the desire to be someone unchanging and independent — leads to liberation from suffering and union with life. Thus, the discovery of one’s true nature and, at the same time, the nature of the universe leads to awakening from the illusion of separateness.

A similar picture of the world can be found in physics. Scientific research increasingly emphasises that the whole of reality should be viewed as a network of relations, which has a dynamic character. It is not a collection of separate, independent entities, but a system of connections forming an integrated whole. According to quantum theory, the material world is a complex and indivisible fabric of events. It also includes the observer and his consciousness. A mystic would say that it is as if the cosmos were looking at itself. In the Upanishads, there appears the famous sentence tat tvam asi, meaning “you are that.” In this way, the division between atman and Brahman, between the human being and God, between the creator and the creation, between the subject and the object, is ultimately transcended.

Today, in times of confusion and instability, we long for a deeper insight into the nature of the world and ourselves. We need new cultural narratives which, based on the discoveries of modern physics, refresh the spiritual insights of our distant ancestors. In these stories, the world is a whole, and everything that exists is an aspect of ourselves. We must recognise that we are all connected, and that every smallest step we take echoes throughout the whole of reality. By observing the world, we have the opportunity to discover who we ourselves are, because its nature is our nature. This is an important lesson on the road toward realising our own wholeness, in which — as a Buddhist saying goes — “a drop of water protects itself from drying out by merging with the ocean.”