What Are You Doing?

"What is above knows what is below, but what is below does not know what is above."

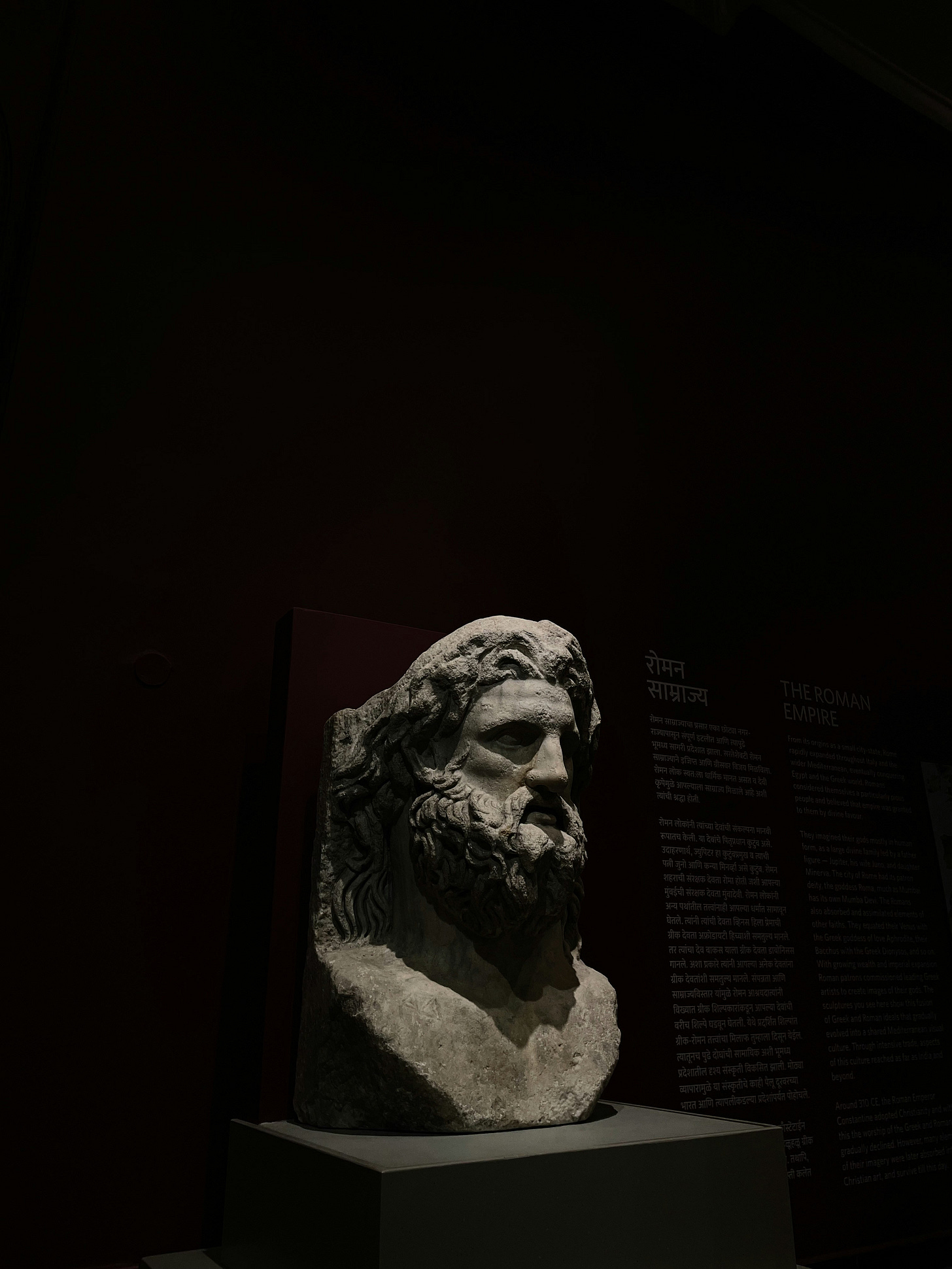

When King Alexander of Macedon reached the banks of the Indus with his army, he found a naked man sitting on a stone and looking at the sky.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“I am sinking into nothingness, and you?” the other replied.

Alexander proudly answered: “And I am conquering the world.”

And both of them laughed loudly, because each took the other for a fool.

There is something eternal, delicate, and quite unsettling—two men with radically divergent visions of success, locking eyes and glimpsing nothing but the absurd in one another.

This story, attributed to an encounter between Alexander the Great and a gymnosophist (naked philosopher) in India, raises a question we often avoid because it destabilises the foundations of so-called ambition: What is foolish and what is wise.

Philosophy has persistently grappled with the inner tension between the ego’s impulse to strive—to build, conquer, and control—and the soul’s quiet yearning to surrender, dissolve, and simply be. The 21st century is saturated with what philosopher Byung-Chul Han calls the achievement society (for its ability to optimise). “The complaint of the depressive individual,” he writes, “is: Nothing is possible.” But perhaps the deeper human fear is: Everything is possible—and still, for so many nothing feels enough.

To sink into nothingness sounds nihilistic at first blush. But look again. The man on the rock isn’t doing nothing—not collapsing, but descending.

Not void as absence, but void as encounter.

In many Eastern philosophies, and increasingly in contemporary existential thought, nothingness is not the negation of life, but its unmasking. To sink into it is to strip away the illusions of permanence, of possession, of a self that must perform.

That’s choosing to dwell where definitions dissolve.

From Nietzsche’s will to power to Lao Tzu’s yielding water, from Kant’s imperative to the Zen master’s emptiness, thinkers across time have tried to answer the same question in different keys: Is the purpose of life to build or to witness?

To sink into nothingness is not to disappear—it is to reappear, unburdened.

In The Book of Not Knowing, Peter Ralston suggests, “What we consider to be knowledge is often just a more sophisticated form of avoidance.” Perhaps that gymnosophist knew that knowledge isn't always power—it can be padding, distraction, the carefully constructed scaffolding of the ego. And so, he let it all drop.

Modern readers tend to side with Alexander. He had action. He had a purpose. He had momentum.

In her 2023 novel The End of Getting It Right, poet and philosopher C.K. Alvarez asks: “What if the soul does not want clarity or closure, but simply to rest in the ungraspable?” It’s a deeply uncomfortable question in a culture obsessed with clarity, certainty, and story arcs that resolve.

The word nothingness has become insulting. People use it to describe burnout, despair, and even apathy. But in many traditions, nothingness is a sacred space. Not an absence, but a fullness in its vastness. Think of the Buddhist śūnyatā, the void that is not void at all but pure potential.

To gaze upward is not apathy. It’s vastness.

Alexander died young. His empire was fragmented. His name became legend, yes—but what did he feel, standing in the silence of his hunger? The man on the rock, by contrast, likely faded into anonymity. But perhaps he died having tasted something truer than power.

Philosopher Todd May, in A Fragile Life, wrote: “Suffering arises when the world fails to meet our hopes… but also when it does.”

What do you do when you have the world at your feet?

Recognise how little we know.

How little we control.

The gymnosophist was lucid. He saw through the performance. Perhaps that is why they laughed—not because one had won and the other had lost, but because in that moment, each saw the other stripped bare. One with a sword, sharp and blood-venging, the other with the vast and peaceful sky.

Metrics?

The milestones?

The conquest?

To let the sky be enough.

To be thought a fool, and not flinch.

To feel the grandeur in a gaze that seeks nothing.

So why bother in the first place?

Just this:

What is above knows what is below,

but what is below does not know what is above.

One climbs, one sees.

One descends, one sees no longer

but one has seen.”René Daumal, Mount Analogue