There Is a Silence Where Hath Been No Sound; There Is a Silence Where No Sound May Be

On The Storks and the Rhythm of the World

Today I’ve been thinking of Thomas Hood’s poem Silence, whose opening words also became the title of this article, and I felt compelled to write. There is a silence where hath been no sound; There is a silence where no sound may be.(…) But clouds and cloudy shadows wander free… Hood’s poem was written in 1823 and, interestingly, was first submitted to The London Magazine in that year, though it was initially rejected. It was published sixteen years later in Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine.

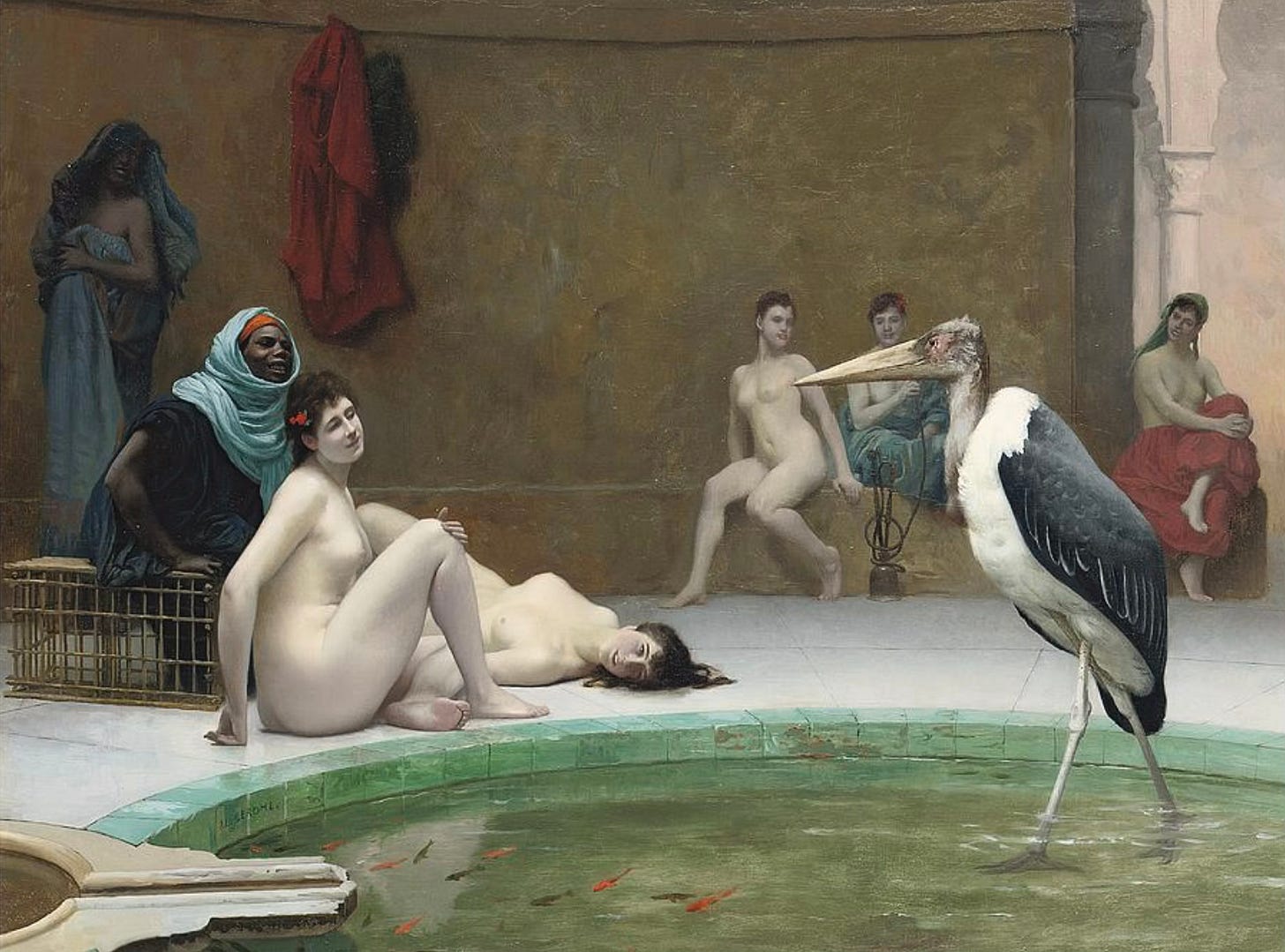

When I think of time, I often return to silence, the silence of the deep sea, and continually between the clouds, the fields, when sound seems to have travelled elsewhere and… to the painting just about it all: The Storks(Bociany), painted in 1900.

In fact, Chełmoński spent decades abroad — in Munich, in Paris — yet his canvases never wandered far from the landscapes of Mazovia or Ukraine: their plains, skies, birds, the simple persistence of rural life.

Here, in The Storks, two figures pause from ploughing. Their clothing takes on the colour of soil, their faces are scorched by the sun and work. And yet their gaze is lifted — to a flight of storks. The birds return as they always have, a herald of spring, of renewal, of cycles. Across cultures, storks have long been more than birds in flight. In ancient Egypt, the saddle-billed stork embodied the Ba, the human soul, and its seasonal return became a symbol of reincarnation. In Slavic pagan belief, storks carried the souls of the unborn from a mythical paradise, Vyraj, to the earth during spring and summer, bridging the seen and unseen. Even in Ukrainian folklore, the white stork, the nation’s emblematic bird, is a messenger of peace and a bringer of life, arriving each year as a reminder that renewal and continuity endure beyond human measure. In Slavic folk belief, the stork was a sacred presence: to see it was to be assured of blessing, of fertility, of safety. Even now, for many, that first upward glance each spring, noticing the return of storks, feels like a contract with continuity.

But it’s not only about the symbol alone. It is that suspended moment, a father and son are no longer only labourers bound to the furrow. They belong to the sky as much as to the field. The father’s face may hold a shade of longing — a yearning for the freedom of wings — while the boy’s eyes rest simply in trust. Between them and the vast canopy above, the silence deepens into something elemental.

Chełmoński gives us not a scene but a meditation: on rest following labour, on presence within anonymity, on time that returns, circling like birds. The Mazovian landscape is stripped of ornament — cottages at the horizon, a fragment of ploughed earth, and above all, an overwhelming sky. It is in this spareness that the mystery resides.

The Storks speak of what cannot be displayed. There is no gesture of self-presentation, no mirror, no inscription. Instead, it invites us into a silence of the invisible order of things. And perhaps that is the opportunity art still lies before us: to stand in its unmeasured expanse.

And yet, silence also invites reflection on perception itself. René Magritte took everyday objects — apples, bowler hats, pipes — and reconfigured them to disturb perception. His paintings highlight the gap between words, images, and reality. Curtains, clouds, doors, and windows recur in his work, suggesting that the visible world is always concealing something deeper, inviting repeated attention and quiet observation. Chełmoński’s peasants and storks, Hood’s silences, and Magritte’s objects all converge in the same meditation:

What is present is never all there is;

what is unseen matters as much as what is seen.

Time in Chełmoński’s painting, similarly to Jean-Leon Gerome’s Le Marabout in the Harem Bath, is linked to the slow arc of wings, the patience and fascination of the observers, that silence where there is no urgency, but reassurance, and enjoyment of it.

Standing before The Storks or Le Marabout in the Harem Bath, one senses that time is layered: the fleeting moment of gaze, the seasonal presence of birds, and the larger span of generations that will watch the same nature marvels after these figures have vanished. Each layer exists simultaneously, folding past, present, and future into a single instant of awareness.

In the end, The Storks and Le Marabout in the Harem Bath ask nothing of us but to meet the rhythm of the world (wider than a single life) without haste.

Interesting read..

Thank you 🙏