The Promise of Boredom

And do we have time for it?

Alone, one feels the whole universe, and none of one’s personality.

- Sheila Heti, Motherhood

I like this idea, I read in a Maggie Nelson essay that making art is the act of trying to ‘become a stranger to oneself’ (paraphrasing Adam Phillips). It’s moving outside the hard limits of your experience, through the medium of your experience, in order to see things anew. That’s the first big potential of silencing enough of the world to experience your own solitude and limitations in a way that feels capacious.

Firing up a podcast or a video or scrolling a feed are all facsimiles for hanging out with other people, thereby curing your “boredom” before it even occurs. As Sheila Heti’s quote above suggests, it is a lack of contrast that opens up creative possibilities sometimes — alone, your personality has no reason to be spotlighted. Nobody else is there, and so you do become the whole universe for a while. There’s your chance to move beyond yourself by seeing yourself differently.

I’m reminded of photographers who spend hours, sometimes days, waiting for the perfect moment to capture an image. Susan Sontag wrote that photography is fundamentally an act of non-intervention, a way of witnessing without interfering. The photographer sits with the discomfort of waiting, of seeing, of allowing another — not own — pace. This is a kind of productive boredom – a state that our hyperconnected culture seems increasingly allergic to.

What is boredom, really?

Restlessness, anxious fidgeting in waiting rooms when you begin to pace up and down and need a toilet break every five minutes? Or the spacious emptiness that follows when all distractions fall away. Perhaps it’s not boredom at all, but rather the unfamiliar sensation of encountering our unmediated consciousness. We’ve become so accustomed to constant stimulation that its absence feels like deprivation rather than possibility.

When was the last time you took a long walk or run without your phone? If you even have such an experience on a list of the biggest regrets of your life, did you mind scrabbled for purchase, flitting between worries, plans, and remembered conversations? Or did you delight in “peace and quiet”? This is what John Cage meant when he said there’s no such thing as silence – only sounds we haven’t learned to hear yet.

Do we have time for “boredom”?

The question itself reveals our cultural bias – framing openness as a luxury, an indulgence to be scheduled between productive activities.

This is what interests me about boredom’s promise. Not the momentary discomfort, but the doorway it opens to a different kind of attention. When we exhaust our habitual ways of seeing and thinking, we create space for the unexpected. The Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto describes his practice as “a dialogue with time.” His long exposures – sometimes lasting hours – transform moving water into misty abstractions, crowded theatres into luminous voids. Time, made visible through patient attention.

Perhaps what we call boredom is actually the growing pains of developing a new relationship with attention. Like muscles unused to exercise, our capacity for sustained, undirected awareness has atrophied.

Henrik Karlsson offers a compelling frame for this discussion in his essay “The Attention Lottery.” He suggests that our current attention crisis isn’t merely about distraction, but about the fundamental structure of how we allocate our attention. Karlsson writes that “attention is a scarce resource, but we haven’t developed adequate institutions for its stewardship.” While we have elaborate systems for managing financial resources—banks, investment vehicles, regulations—our attention remains vulnerable to exploitation by the highest bidder.

What strikes me about Karlsson’s perspective is how he recasts boredom as a form of attention wealth rather than attention poverty. When we’re “bored”, we possess an abundance of unallocated attention—a surplus that could be invested rather than squandered. This inverts our conventional understanding.

Karlsson further argues that “attention is relational”—it exists in the space between perceiver and perceived. This echoes what phenomenologists have long maintained: consciousness is always consciousness of something. Perhaps this is why solitude can feel simultaneously empty and overwhelming. When external demands recede, we confront the raw fact of our own attending. The question shifts from “what should I pay attention to?” to “how am I attending at all?”

I find particularly useful Karlsson’s distinction between directed and undirected attention. Directed attention—focused, goal-oriented, evaluative—is what our economy values and rewards. But undirected attention—wandering, receptive, non-instrumental—may be more fundamental to human flourishing. It’s in these open states that connections form between previously unrelated ideas, that we notice what we weren’t looking for.

Consider how children attend to the world before they’re socialised into productive attention. A child can spend an hour watching ants, not to learn about entomology or to accomplish anything, but simply because ants are fascinating. They can lift up to 50 times their body weight, equivalent to a human lifting a truck. They build living bridges with their bodies, creating complex structures that allow their colony to cross gaps efficiently. Something we, as humans, could learn from: The Argentine ant supercolony stretches over 3,700 miles across Europe, comprising billions of genetically similar ants that recognise each other as family rather than fighting as territorial rivals. Certain ant species practice sophisticated agriculture, cultivating fungus gardens that they fertilise with leaf cuttings and protect with antibiotics produced by bacteria they cultivate on their bodies. Perhaps most remarkably, ants have existed for over 100 million years, surviving the extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs, evolving complex social structures that rival our own in organisational sophistication.

When we slow down enough to notice, the world teems with wonders that escape our usual categorisations. The simple ant challenges our assumptions about intelligence, society, and even consciousness.

I’m reminded of E.O. Wilson, the renowned myrmecologist who devoted his life to studying ants. His attention wasn’t merely scientific—it was a form of devotion, a way of being with the world that transcended utilitarian knowledge-gathering. Wilson described watching ants as “a glimpse of eternity,” noting how their social structures evolved over millions of years before humans walked the earth.

This type of sustained, wonder-filled attention feels increasingly countercultural. We’re conditioned to extract value quickly—to ask “what’s the point?” before we’ve allowed ourselves to fully encounter what’s before us. The market logic of efficiency infiltrates even our most private moments of perception, the spaciousness of not-knowing, of being-with rather than using-for.

This capacity for absorption without agenda is what artists and scientists try to recapture—the ability to see without immediately categorising, to experience without instantly evaluating.

Karlsson suggests we need “attention sanctuaries”—spaces protected from commercial exploitation and optimisation imperatives. These might be physical locations (libraries, parks, retreat centres) or temporal practices (meditation, art-making, deliberate technological sabbaticals). What unites them is their creation of conditions where attention can operate according to different rules.

I’ve been experimenting with what I call “attention fasting”—periods where I deliberately restrict my information diet. Not to increase productivity, but to discover what emerges in the absence of constant input. After the initial withdrawal symptoms—the restlessness, the phantom urge to check nonexistent notifications—comes a gradual recalibration. My attention becomes less fragmentary, more patient. I find myself capable of sustaining engagement with a single thought, image, or sensation for longer stretches.

Have you been re-drawn to photography recently? Not the compulsive documentation that social media encourages, but the slow, intentional seeing that photography at its best demands. The camera forces a relationship with time that feels almost archaic in its patience, a fertile void where attention can rediscover its natural rhythms. In allowing ourselves to be “bored,” we might reclaim the sovereignty of our perception from the forces that would monetise and manipulate it.

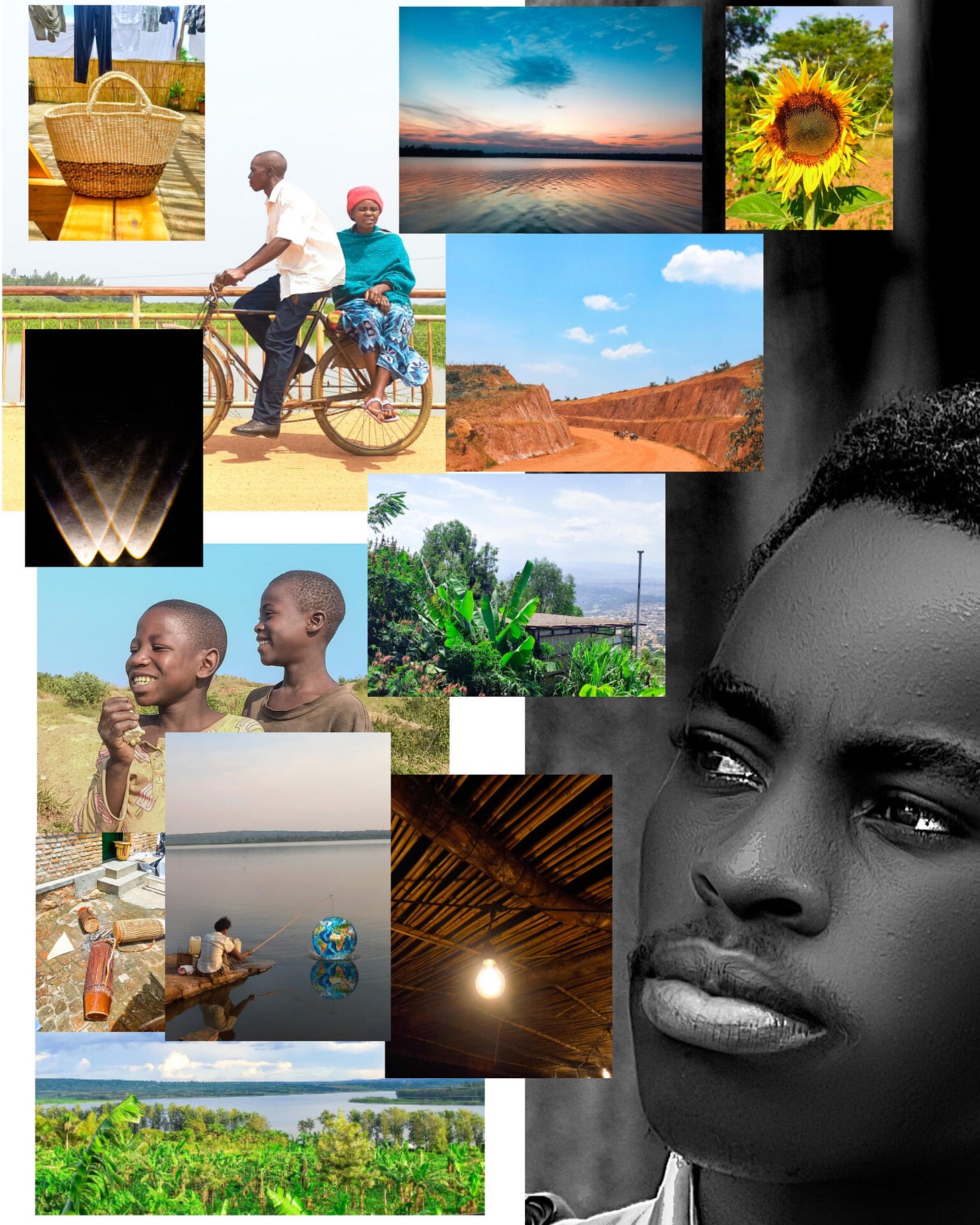

Thank you to GARBIEL SHUKURU for his photographs accompanying this article.

I see the need for info overstimulation (whether through social media or simply “oh, just let me read that article in case it helps me with work”) as nothing other than addiction.

Some seek it to self-regulate, others to numb… because boredom might feel too exposing and reveal how unbearable and heavy life can be to a nervous system that doesn’t know how to metabolize experiences.

And as a chronically online human who spent more than 2 decades in front of a screen (should consider myself a pro at info consumption, haha), I can say the worst part about it is… you start experiencing life at the pace and speed of information, mostly living in your head. And that’s the real danger of it.

Days without info overload feel much heavier, slower, and somehow, real.