OH, COME ON! NOBODY’S FAVORITE COLOUR IS BROWN!

Mine is!

Last month I was about to give an interview, where I was almost asked a question: What is your favourite colour? I am glad the producer changed the format of the program, treating a conversation with me as a subject in itself that doesn’t need an initial entertainment bit.

“Earth colours are voices from the very soil on which we stand,” wrote art historian Michel Pastoureau in his seminal work “Brown: The History of a Colour.” “They speak of permanence, of covenant with the land, of promises kept through millennia.”

Indeed, while brown began as the colour of the humble, its richer cousin marron (chestnut brown) found its way into the chambers of nobility. In the courts of Renaissance Europe, the deep, luxurious hue of marron became a statement of refined taste. As textile technologies advanced, the ability to create consistent, rich brown tones represented mastery over natural pigments.

The poet John Keats captured this transformation in “Endymion”: “Now while the earth is dressed in Autumn’s mood; In all her browns and yellows, dull and bright.”

Throughout literary history, brown has symbolised covenants with the earth. In Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” the brown dust of the road represents both struggle and homecoming. “The road was full of turns and curves,” Morrison writes, “so that looking ahead, they couldn’t see what was coming.”

Artist Anselm Kiefer, known for his earth-tone palettes, once remarked, “Brown is the colour of covenant — between heaven and earth, between humanity and its origins.” His massive canvases, laden with brown soil and organic materials, speak to ancient promises between humanity and the land we inhabit.

The Quaker movement, with their “plain dress” of brown and other undyed fabrics, established a covenant of simplicity and honesty. Their choice of brown wasn’t merely economical but a deliberate statement against vanity — a promise to value substance over appearance.

The phrase “brown study” — meaning deep thought or meditation — emerged in the 16th century, linking brown with intellectual contemplation. Libraries with their leather-bound tomes in varying shades of brown became sanctuaries of knowledge. As Virginia Woolf noted in “A Room of One’s Own”: “The brown leather volumes, the gilt lettering — they speak of permanence in an impermanent world.”

Fashion designer Phoebe Philo revolutionised the use of brown in contemporary couture, noting, “There’s a richness to brown that speaks of authenticity. It’s not showing off; it’s showing up.” Her collections for Céline elevated earthy tones to luxury status.

We humans perceive the colour brown probably more than any other on a daily basis. It’s everywhere: it is the most common eye, skin and hair colour in the world; it’s widely found in the natural world — in earth and soil, plants and trees; it’s the colour of much food and drink, such as chocolate and coffee. Pigments for brown are also among the oldest: paintings using raw umber — a natural clay pigment — have been found to date back to at least 40,000 BC.

In the realm of textiles and clothing, brown became the colour associated with the humble and lowly across Europe. In the Middle Ages, brown robes were worn by Franciscan monks as a sign of their humility and modest lifestyle. And what began as probably a means to get by (coloured inks were more expensive and brown vegetable-dyed cloths were cheaper to produce), became a stamp of social standing. In Ancient Rome, brown clothing was worn by the citizens of low classes and even those considered to be ‘barbarians’. The old term for an urban poor civilian, ‘pullati’, literally translated as ‘those dressed in brown’. By the statute of 1363, lowly working-class English citizens were required to wear russet, a coarse woollen cloth that was dyed with woad and madder to turn it grey or brown.

One of the most unusual sources of brown is that of sepia. The term comes from the Greek word for cuttlefish. A reddish-brown pigment has long been created from the ink sac of a species of cuttlefish since the Ancient Roman period. There are consequently subtle differences between sepia shades, due to the various diets belonging to the cuttlefish depending on where they were found, and also where the inks were made. Sepia has been used since as a medium for drawings — most famously, Leonardo da Vinci used sepia-toned coloured washes — and later still, sepia became the term given to the method of toning photos with a faded brown tint. This process uses chemicals such as sodium sulfide or polysulfide toners, and today a sepia effect can be achieved digitally with duotone — a method that combines a grayscale image with another colour.

Sepia, most commonly associated with the colour of old photographs, which were treated with a sepia wash to give them a distinctive, warm brown tone that proved more stable than pure black-and-white prints.

A second surprising — and rather morbid — source of brown pigment originates in the medieval period, when the remains of mummies were ground up for archaic medical procedures (potentially due to them containing the substance bitumen — believed to have medical powers). During this process, the rich consistency of the powder was observed, but it was later, during the 16th and 17th centuries, that a paint source was created from the ground-up corpses of exhumed Egyptian mummies (both humans and cats). It was known as ‘Mummy Brown’, and was given commercial status as artist’s paint.

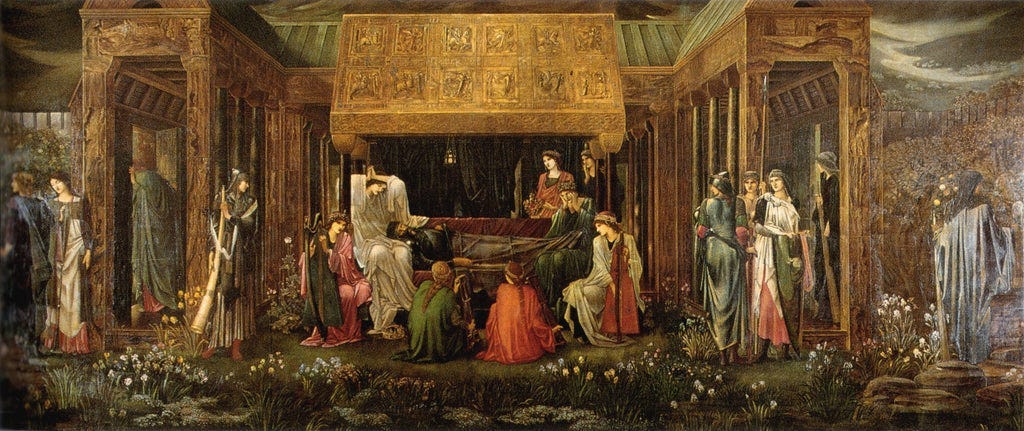

Mummy Brown was particularly popular amongst the Pre-Raphaelite painters of the mid-19th century, such as Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The ground powder would be combined with myrrh and white pitch to produce a brown pigment. Its transparency meant that it was a good medium for glazes, shading and colouring natural flesh and hair tones. Used until the Victorian era, Mummy Brown dropped out of favour as it became more expensive, and when artists began to realise how the pigment was sourced (Edward Burne-Jones was rumoured to have buried a paint tube of Mummy Brown in his garden when he found out). Its story doesn’t end there, though. Mummy Brown took an even more macabre turn when demand surpassed supply, and people were found to have made black market versions of the pigment from the ground powder of recently deceased corpses of criminals or slaves. If you come across the paint today, you’ll be pleased to know that the pigment is now made up of quartz, kaolin, goethite and hematite.

After its popular use among Renaissance artists, brown was utilised by subsequent painters in a monochromatic way. It became an important colour for realism in portraiture — in shades such as Burnt Sienna and Burnt Umber — and to create shading and in subtle shifts from light to dark. During the 16th and 17th centuries it became common to paint onto a surface that was tinted brown, rather than white. Dark pigments, including that of brown, were significant in Rembrandt’s palette. He favoured Vandyke Brown when sketching out initial compositions of paintings, using it in combination with other earth pigments to give his works their recognisable broody, dark background glazes. Named after Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck, who also regularly employed the shade, Vandyke Brown is most often made from bituminous earth or a black pigment mixed with calcined natural iron oxide.

Today, brown’s sombre and lacklustre past has been turned on its head, as the colour is increasingly associated with the rise of sustainable and eco-friendly products, from bamboo toothbrushes to recyclable cork to brown paper bags. When brands are using brown in their visuals, they are targeting an audience made up of people who are tuned in to the climate crisis and ecologically aware of lessening their impact — think organic products, refill shops and recycled goods. What was once deemed as ‘lowly’ has come full circle. Brown’s resourcefulness, availability, low cost and cohesion with the natural world have made it a colour of ‘less than’ in the past, but it is precisely this that has made it one of the most important colours in the modern world, helping to push forward environmentally ethical change.