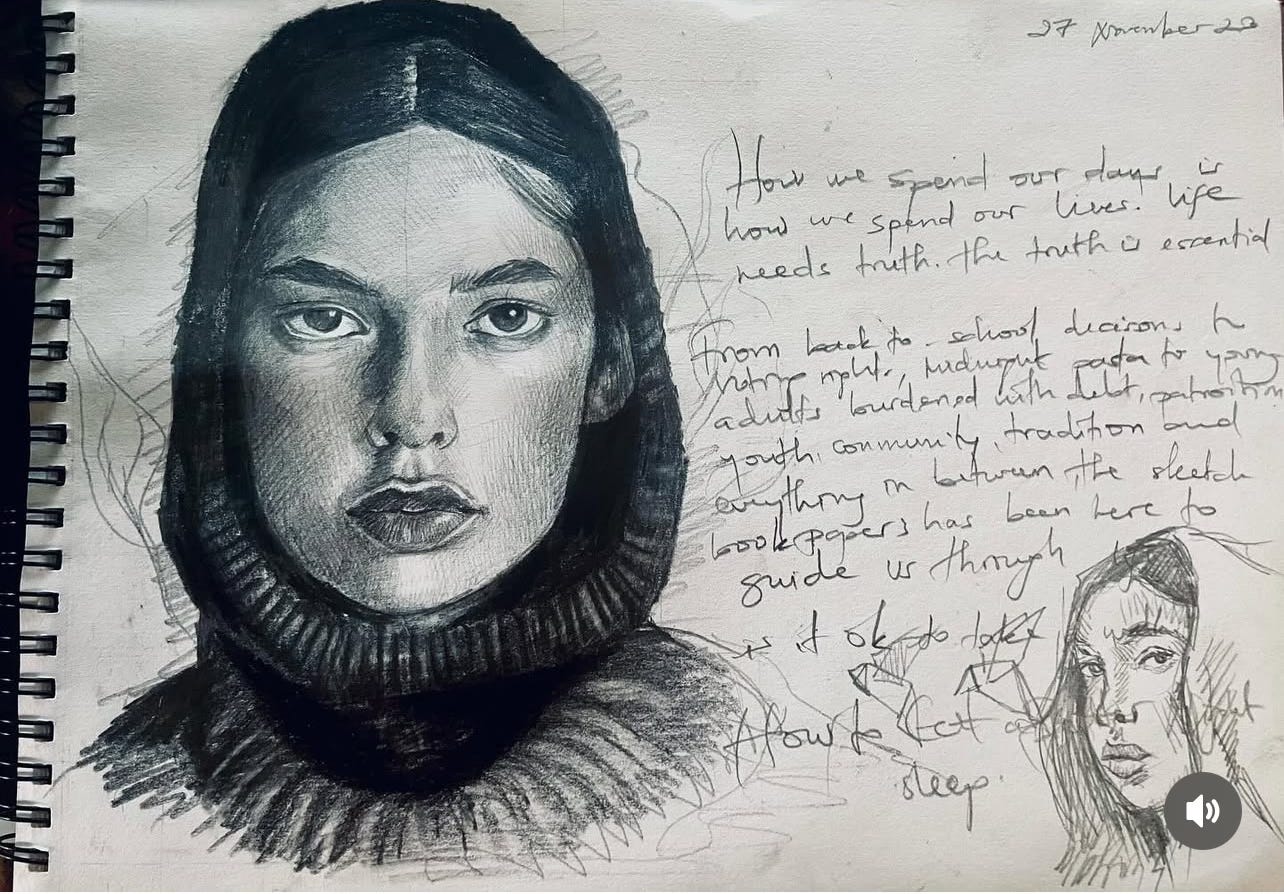

Need for Old and New Roots

Names tell stories. So does my last name. Far from understanding its notions in Japanese, from Egypt, to as far as I know, central Africa the meaning of the name Atsu is: twin and sometimes even more precisely—twin if it is a boy. My maiden name, in contrast, means something like girl/pretty girl or kerchief in one of the old dia…