He has nothing — not even a T-shirt, but he still has hope: A Conversation with FLORENT MWARABU

I will begin with something that isn’t standard. So maybe you’ll feel a bit uncomfortable, because it’s not the kind of question that’s usually asked. If you want, you can answer; otherwise, we’ll change the question, okay?

Yes, let’s try.

Okay, so when you woke up this morning, a Congolese national, but resident in Burundi, what did you think about? What was the first thing you did?

This morning, when I woke up, I was thinking about what I was going to do and where I was going. I’m going on holiday, but it won’t be completely a holiday because I’m going to another country. I thought about what I could create, what I could do there, how I could enjoy it — because it’s not easy to leave our country and go to another one. For us here in Africa, it’s really not easy; it’s something difficult.

So, I thought about trying to create something, to build a network. I thought about taking my works with me and trying to create something there, to make the most of it.

And where will you be travelling?

I’m going to Uganda. From Burundi.

You said you want to create something. Is that instinct to create — wherever you are, wherever you go — part of who you are? Or is it more about being useful, using the moment to gain experience, visibility, recognition?

Yes, that’s it exactly. Visibility, recognition, and creating a network. Starting with a continental network is much better for a career. For us, especially when we have the chance to travel like this, we take advantage of it. I am talking to the Ugandan artists — creating a network with them — it’s something many people never get the chance to do. To move, to go somewhere else. So it’s about networking, recognition, doing as many things as possible. Creating an exhibition with them, growing the portfolio — that kind of thing. I’ll work with a man here who does acrobatics. I’ll talk to him, I think.

I want to create something here first, then let it grow.

The inspiration will come.

Maybe from myself, maybe from there.

Creating an exhibition will take time; it all depends on how the conversations go with the people I meet there.

But I’m ready and open to everything: artistic collaborations, galleries in Uganda, new contracts — everything.

You have more than four years of experience.

Since 2020, I really started drawing professionally. Before that, I enjoyed it since childhood. I even helped with organising drawing competitions and exams. Even when I was a student myself, I’d take part in an exam I helped to create. So from a very young age, drawing was already there. But professionally, it started in 2020, and I was never an art student.

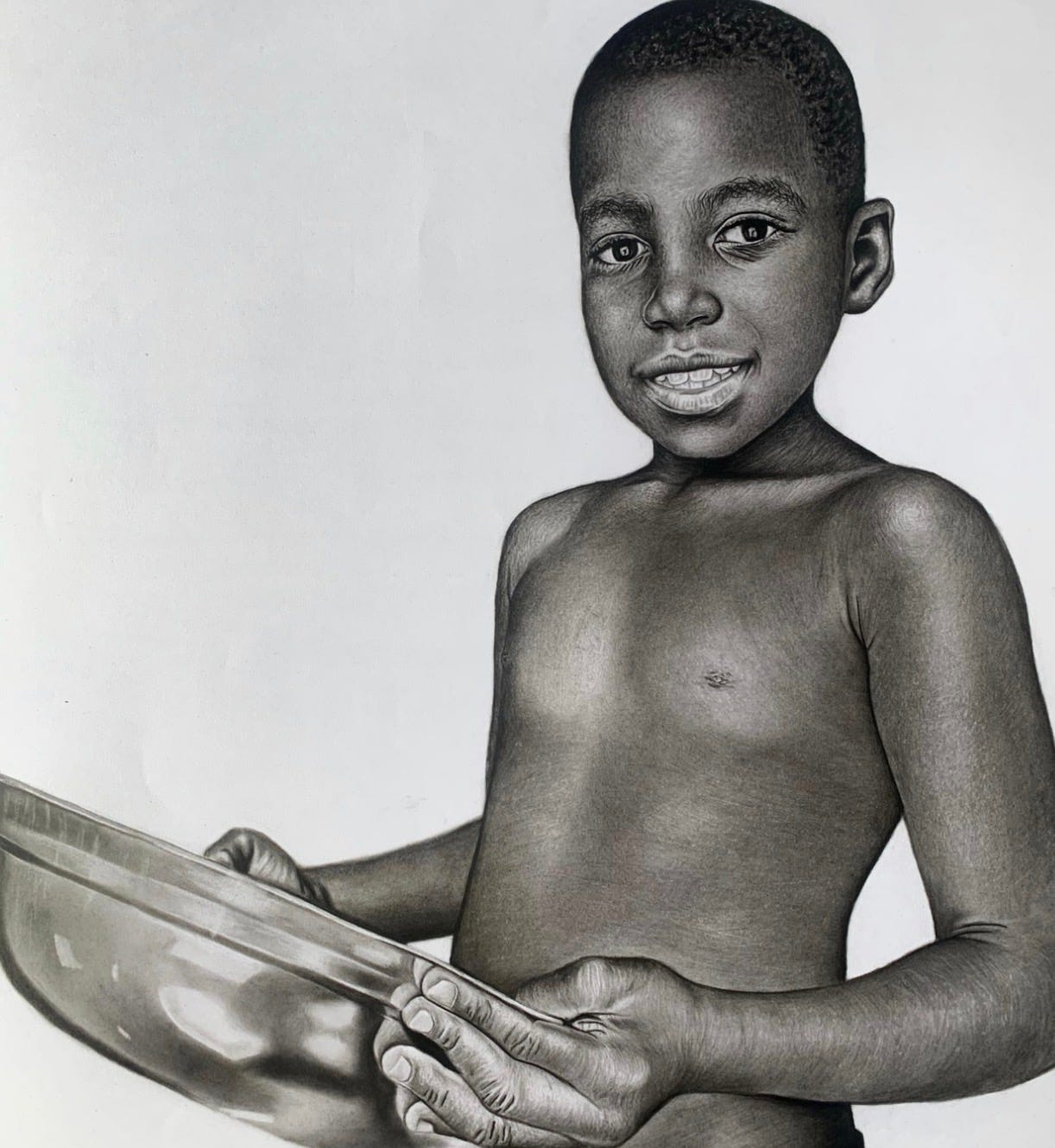

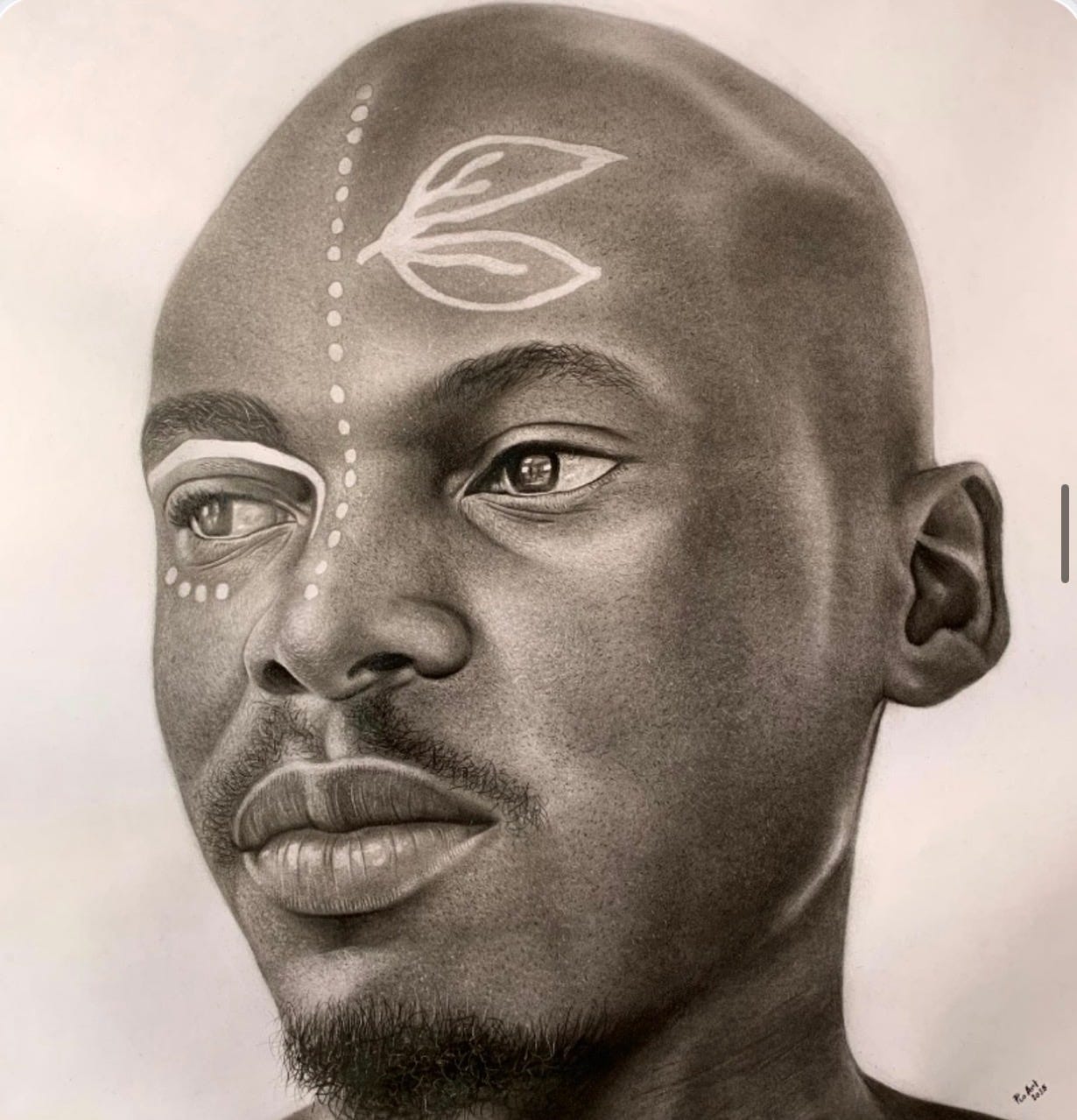

Now let’s talk about your artworks. Let’s start with this piece, Idéalisme. Where does the idea come from?

This work talks about identity. African identity, especially. Our children here don’t live in the same world as children in Europe.

You see the empty plate — that’s important. That’s why I called it Idéalisme. He’s developing ideas on his own, without guidance. He doesn’t know who he’ll become, how he’ll start, which path he’ll take to become who he wants to be — or who he believes he is. But he keeps going.

There’s hope. There’s a smile — a confident smile. He tells himself that one day he will become something, one day he will have something. That’s why I represented it with the empty plate. He has nothing — not even a T-shirt like mine — but he still has hope. That’s the idea behind it.

So the plate symbolises lack, and he’s full of hope and aspiration?

Yes.

What emotion do you want to evoke in the viewer?

It’s like a call for support.

When we see these children — many of them living on the streets — they are children who lack material things, but they are incredibly intelligent. Truly intelligent. Often, more than children who grow up wealthy.

They have hunger, desire, and ambition. So when we see these stories, it pushes us to support them, to help children who believe they can become something. That’s it.

Are you speaking a little about yourself in this work?

No. I’m speaking about what I’ve seen — what I see now. Burundi is one of the countries with many street children. We see this everywhere: on the way to university, in the streets. As artists, we have to try to do something.

I think it becomes another job for artists. As they grow and practice their art, they see that many others could do it too, but there’s a lack — a gap, as we say in English. Talent alone isn’t enough; some conditions need to change, and we can help change.

Let’s talk about Naître digne — Born with Dignity.

That was the first work I created when I arrived in Burundi. It’s a tribute to childhood and growth.

You see the hand pouring water — the source of life. It speaks about rights: the right to education, the right to life.

The water represents education and all the good things. The large hand pouring it symbolises the responsibility of adults, of society.

A child can’t give themselves an education;

it’s their first time living.

They must be guided.

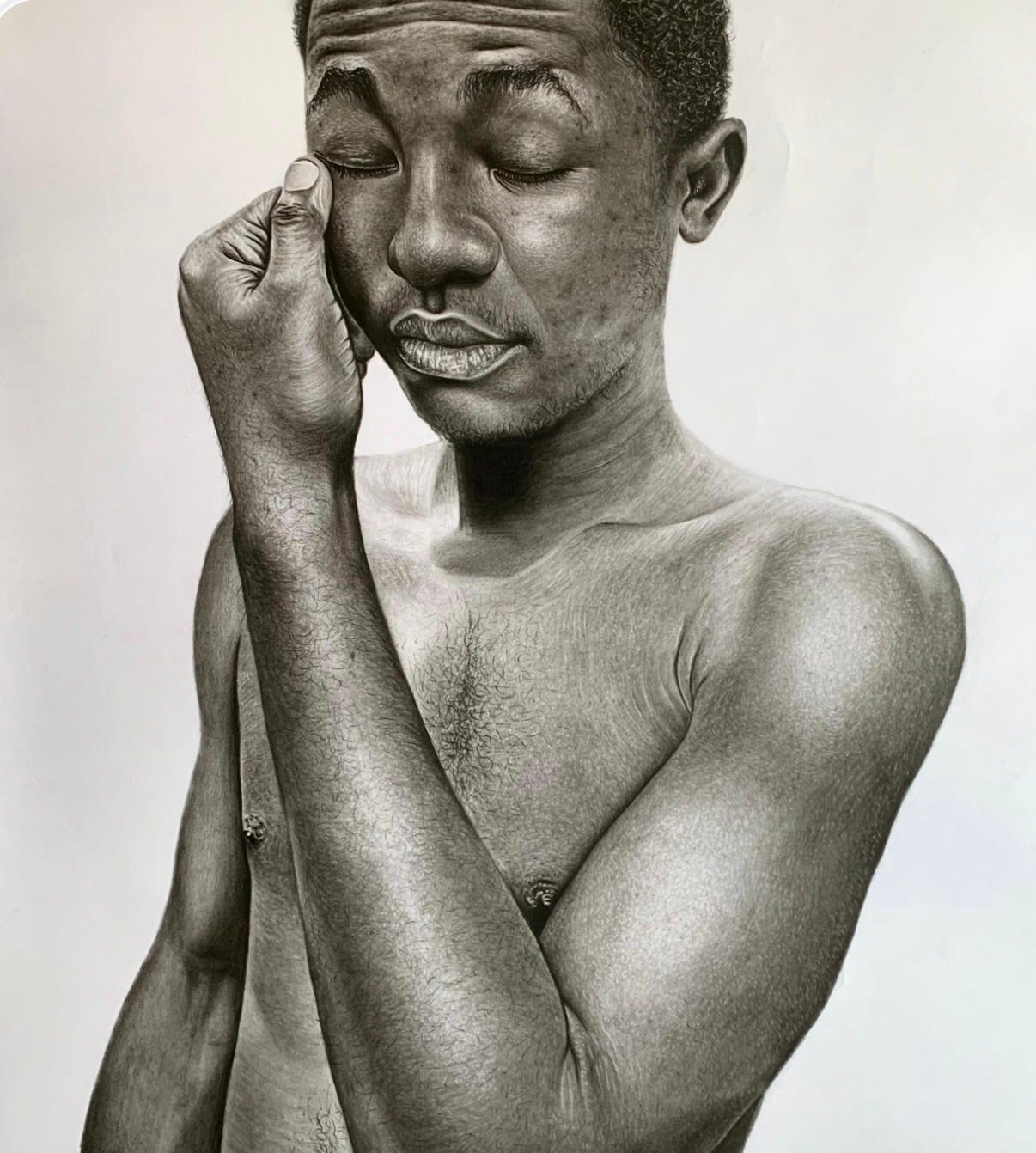

And Résignation?

“Résignation” is something else. That one is more about me. All the people you see in my works exist — they’re around me, friends, people I know. I created Résignation during a moment of chaos. I was preparing an exhibition, but I was down. I couldn’t work anymore. I had no resources to continue.

I still had hope. I prayed and worked at the same time. Résignation was a decision taken when the mouth can no longer speak, when you can’t express yourself anymore — but inside, you tell yourself you can continue, without panicking.

People saw the exhibition, but they didn’t know what had happened inside me — financially, emotionally, everything. After that resignation, I got up and continued working. And now, honestly, I feel like I’m entering another resignation. I’ve been down for some time; I haven’t worked for a month. But I believe I will work again soon.

Where does that inner calm come from?

It depends on the person. Everyone has their own way. For me, going somewhere I like, visiting someone I care about, going to a museum or cultural space.

When I see others succeeding, it gives me strength.

I tell myself: that’s my place too.

I need to stand up and work.

How is access to art in Burundi today?

It depends. Many people focus on portraits and commissions. I do them too, but I don’t think it’s a good long-term path for an artist.

An artist has a mission: to create a world, to transmit something, to build exhibitions. Portraits decorate homes, but they don’t always serve that mission.

Art requires patience. You might not be visible — the work is in front, not you. Many young people don’t like being invisible. And it’s not something that pays quickly.

I started in 2020. Maybe I’ll sell a work that supports me fully in 2035. Until then — how do I live?

That’s why I study telecommunications and IT. I combine it with art: graphic design, video editing. If art smiles, great. If not, I work. That’s how you survive as an artist here.

And Rouge intérieur — Inner Red?

That was a moment of fire. A period when I couldn’t work anymore. I took a photo of myself in my room and drew it.

It came before Résignation. First, there’s the inner disturbance, the discouragement, the fire inside. Then comes resignation. It was a strong moment — a whole collection.

I didn’t go to art school. It’s a gift. I discovered myself in 2020 — learning shading, detail. I learned by working with others, older artists, tutorials. There is the Academy of Fine Arts in Congo, but I couldn’t afford it.

Difficult moments have no age. When you’re a child, not getting candy feels hard. As a teenager, heartbreak feels hard. As an adult, money problems feel hard. It evolves.

Perspective changes. So what you’re telling young artists is that this passes — it’s a phase?

Yes. Exactly.

Patience is everything — not just to start, but to finish. Many artists are depressed because they expect talent alone to be enough. It isn’t. You need work, networks, courage to write to people, to apply, to show yourself internationally. Social media matters. You must work on your network as much as your art.

Many people are afraid to write. But you must. Even if they don’t reply the first time, insist. That’s how things grow.

Art is inspiration, collaboration, reaching beyond your reality. That’s how we move forward.

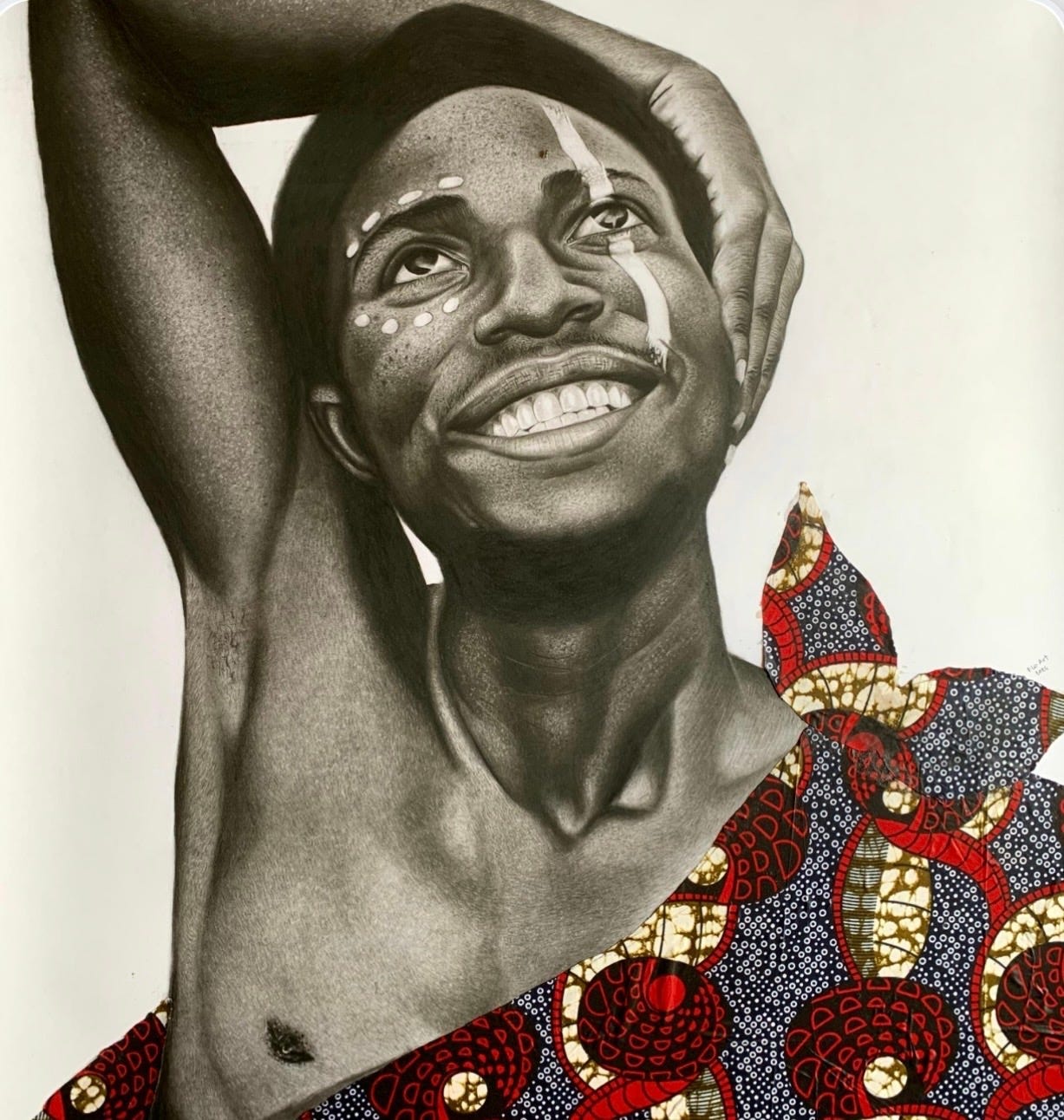

Let’s talk about Bomoko. In Lingala, that means Unity / Union.

Yes, yes. This resistance is what it actually describes.

I love everything that’s in the piece. And in fact, there is the pagne — the traditional cloth. I made the pillows with the pagne that’s on the right side. That’s why every time I see something like that, it immediately touches me. I even have a book — when I read it, honestly, it’s very good — We Are All Birds of Uganda. The first version I read had a different cover, but this cover has that pagne. I don’t know if you can see it, but it shines. When I saw it, I said, “Mama, I already love this.”

It’s a work that many people loved — Bomoko. Yes, it’s a piece that really resonated with many people. People say, “We really love it.” It’s cool, it’s traditional, it’s collective — even for me. Normally, it’s a work about crisis, but above all, it’s about African unity among Africans. I don’t know where you are right now, but you experience this unity among Africans wherever you are. That unity is always there. Because the pagnes in the background represent unity: they are different fabrics, with different patterns, connected together. Pagne is something you find in Africa — it’s made mostly in Africa. It’s one of those deeply traditional African elements. I wanted to illustrate that in the background — these fabrics touching each other. That’s what it shows: African identity. How we are united everywhere. That unity is felt even in the West — everywhere, everywhere in Europe. That’s why this artwork exists. Why do you find this piece incredible?

Because of the hands — at first, I don’t know why, I thought they were feet and hands. When I saw it for the first time, I was confused. Then I understood the posture — it could only be the hands.

Your inspiration — because you said it comes from the people around you, from yourself, from inner processes, emotions, the passage of time — everything that is shared by all of us. And beyond that, what other inspirations do you have?

Inspiration — this is something more personal. It depends on how each person lives their own story, everything they go through in life. For me personally, when something bad happens to me, or something hurts me more deeply, I’ve noticed — especially recently — that when something painful happens, I become very inspired.

Many difficult things happen to me, but it is precisely in those difficult moments that I feel more inspired.

There are also moments when I go to green spaces, places with open air. There is the city everywhere, but I go where I can breathe, and there I feel inspired, in nature, places like the beach. That’s where I feel inspired. So it really depends. For me, that’s what being inspired means.

So tell me: when you’re at home, where do you usually go to feel comfortable, to breathe, to pass time — not to make art, but just to be yourself?

I spend most of my time at the beach, by the lake. There is a whole neighbourhood there with two beaches. You may have heard of Lake Tanganyika. There are beaches, waterfalls, and almost everything.

Yes, there is real calm there. Burundi has its bars, cafés, and bistros are not very noisy like in Congo. People are calm, they drink quietly without disturbing others. Outwardly, everything is calm — even if inwardly people may be troubled. But that calm allows everyone to reflect, to take time, to concentrate.

You are very young, and you taught yourself — through YouTube, like many of us — how to do certain things. So we can say you are very independent.

Yes, totally independent, because necessity forces you to be.

There is no other way — no one comes to hold your hand and say, “Come, learn.”

So you learn to make use of available resources. Where we are born, we learn to be self-sufficient.

Were there relationships in your personal or professional life that really supported you? It could be your mother, an artist who spoke to you, or another important figure.

When it comes to relationships, I really value lived relationships — real relationships with people. First of all, my parents, because they are the first people. Then my friends from the Academy of Fine Arts, friends who are still there now. We share almost everything. There are my parents, my friends — many friends.

Even though I didn’t have the means to attend the Academy, I stayed connected to those who are there. We spent good times together, lived in the same city, shared new things. They tell me what’s new, what’s happening — other artists too: Jean-Luc, almost everyone. They share their experiences with me — what they live, how they exhibit, their new ways of working.

These are people I will never forget. They really help me in my career. Many people don’t see the difference between me — independent — and those at the Academy. But we share the same values. We work almost the same way. We have the same mission. It’s really thanks to them that I do so much and discover so many things.

And what are your artistic dreams?

My artistic dreams were once very unclear, especially considering African realities and everything we live. But now, as we start gaining visibility and recognition — respect, even — we begin to see change. People call you “artist.” You go to university, to public places, and people show respect.

That gives me courage. It’s something worth pursuing to the end — especially internationally. When you pursue something, you first have to look at your immediate environment. That’s something entrepreneurship teaches: start locally. See if it works. See if your efforts lead somewhere.

Today, we see great artists at home who still end up in poverty. It happens everywhere. Many great African — and especially Congolese — artists have made a name for themselves, are respected, but still live poorly. No one lets them walk on foot, yet they don’t even own a car.

So we should copy their work — but not copy the choices that led them into poverty. I always make the effort to learn from others’ work, but not to copy their path. I have my own sensitivity, my own way of creating.

It’s not about fleeing the country or denying nationality. I love leaving, going somewhere, working, doing great things — and then coming back to invest at home. That’s what I want. Because staying only means stagnation. But if you leave and return, you bring something back to your society — something that helps younger people who follow you. You become an example.

There is this Lingala proverb: EBALE ENTENGAMA PO EZANGAKA MOTEYI. The river got crooked because of a lack of an adviser.

You started well, I’ll expand on this favourite saying of yours.

This is just one of many wise Lingala sayings— there are many. The world is in need of mentors, advisers, even seers — and if they’re not there, that’s when we struggle, because it can take us much longer — much longer — to find our path, right? Is that it?

Yes, that’s it. If you don’t pay attention, you’ll end up like the riverbank. You see, the riverbank is never straight, never level; it’s always slanted. And if you lean only to one side, you’ll find yourself lost.

Today, the artistic world is a risk. Being an artist is a risk. I think even working in communication today is a risk. We accept taking these risks. But if you’re not careful while taking them, you’ll become tilted, unbalanced.

So we’re obliged to follow certain paths, certain directions, guided by elders, by those who came before us. Personally, I don’t know — I’ve always been guided by elders. I try to consult some, even those who aren’t drawers or artists. In Congo, being an artist — it’s almost like an illness. Most of our great artists often end up poor.

There are people who can walk — who should never have to walk long distances on foot — there will always be people to help them, yet they themselves don’t even have a car. You see that kind of person? They have the touch, they have everything, but there’s something they didn’t do to reach the level they should have reached. That’s what it’s about. These are people to learn from — but also people whose mistakes you shouldn’t repeat. You have to do something different.

There are also others who call themselves producers and so on. We try to understand them, then we try to follow them. I told you at the beginning, too:

I’ve always had people at the academy, everywhere, guiding me.

They tell me: no, this weakens here, do it like this, like that. They guide us constantly. Among young people, that’s how it works. And it really helps in a course of study, in a career.

I think you touched on a very important subject: having talent without help. Either it’s advice or practical help to get where you’re going. Yesterday I watched something where an actor — a professional — said that what’s missing in the education of artists today is someone saying: I see you. I think you’d be good at this. I see you in this profession. You have something vital. Like a seer who sees talents, who sees where we can go. What he said was that young people going to artistic schools — actors, artists — get greeted by this very old mentality of pushing them down, making them like new soldiers in the army. I don’t know if you know that practice of crushing people — breaking them — thinking something good will come out of it. He said he disagrees, and I agree too. They crush you, show you that you’re nothing, that you’re worth nothing, and they call that education. But that’s not the method. I don’t know anyone who was told they were useless and then grew up strong and confident. We’re missing elders who say: Yes, you’re not perfect, but I see you here. I see how you could get there. Another thing he said is that what we often hear when we’re young is: That’s too difficult. That’s impossible. That business is too hard. From the very beginning, you’re discouraged, made to feel guilty because it’s “too difficult”, you will never get there.

That’s how it is. In Africa, when a child isn’t considered intelligent at home, they’re sent to draw.

And today, the way artists dress — letting their hair grow, for example — people see them as crazy. At least they have hair, they say. Contemporary fashion, copied by many artists, makes the story harder for spectators and outsiders to understand. They always say we’re crazy. How do you manage? You create a world, but look at your hair. All of that.

So there’s a distinction between what’s considered reasonable — technical jobs, useful things — and those “crazy” people who don’t fit anywhere, who produce strange, incomprehensible, mad things. And yet, young people are actually very intelligent, because they make things that the old generation tries to discourage. One of the questions children ask each other in my culture — because we don’t really have small talk —is: Are you more humanistic or more scientific in the way you think? We asked that when we were young to see where we were oriented, where we functioned best, where our capacities lay. People can see, for example, that you have two sides: a technical side that you use for earning a living, and an artistic side that’s more about vision. And you want to combine them. That’s what many artists actually are. If you only have one side, in many circumstances, it is hard to survive.

It’s something to fuse, something to combine.

That’s why we need culture, training, broader education — to mix things.

In art, there’s entrepreneurship: knowing how to sell your work, knowing ethics, knowing how to talk to clients, and knowing how to communicate. You’ll do interviews, public appearances; you need leadership. All of that is important.

As artists, we have to work on all these points and neglect nothing — technical skills, video, everything. For a start, it’s always difficult. You can’t have everything from the beginning. You need at least a base in everything, and then people will come.

A message and encouragement for young artists…

So encouragement to everyone who aspires to art — and I’m not speaking only about drawing, but art in general.

To those who are new to art, who are inspired, who breathe visual and contemporary art, my message is: work, persevere, and above all, be patient. Do a lot of research. Work.

I might even be an example myself. People ask whether I had training — I had none. It came through work, through searching, through curiosity, through teamwork.

And finally, what can we wish you for the future?

For my career? I want to combine drawings with performance, creation in big spaces, and collaborate with major personalities. I think I’ve already taken a step— that’s already something. The essential thing is to keep working, keep researching. Work alone isn’t enough; you have to mix things. I also plan to study, because talent alone isn’t enough. I need structure, knowledge. Sometimes we work without even knowing what we’re doing, and others use technical terms we don’t understand. Yet we do it well. That’s why education matters.

I want to go further, work with great people, become a role model, especially because we still have many “rivers” to straighten.

Where I come from, it’s rare to see that. People see my photos on social media and think I’ve already made it, that I’m already living a higher life than they are. But in reality, we’re still working.

To learn more about FLORENT MWARABU and his upcoming projects, please check his profile: