Every outline is a fiction; the world itself has no edge

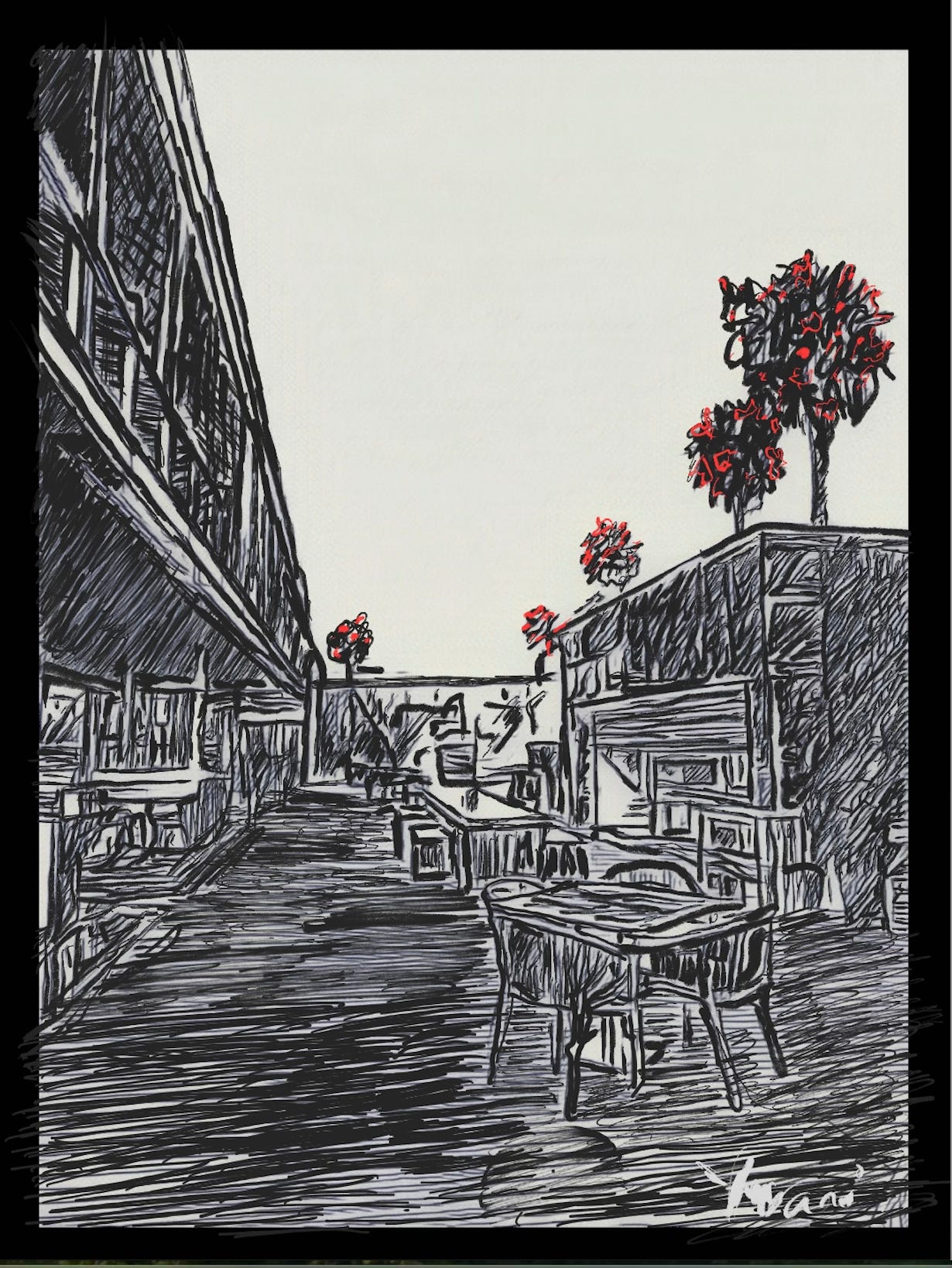

“Always lines, never forms. Where do they find these lines in Nature? Personally I see only forms that are lit up and forms that are not, planes that advance and planes that recede, relief and depth. My eye never sees outlines or particular features or details… My brush should not see better than I do.” — Francisco Goya

The line is not real in itself. It is an invention — a shorthand, a way of capturing what the eye cannot hold in its raw, shifting fullness.

Lines, of course. Nothing but lines — my eye never sees outlines.

Goya, court painter and chronicler of war, celebrant of Spanish festivals and witness to their brutality (Los Caprichos, The Disasters of War) knew what the line hid: reality is not a clean border but a shifting plane, advancing and receding.

Hans Sedlmayr, the Austrian art historian, once wrote that modern art “tears down the frame, erases the contour, and exposes us to the infinite.” Goya anticipates this, suggesting that to trust in lines is already to believe in a fiction.

So why do we keep drawing in lines? Why do we believe in fiction?

The line is the simplest agreement we can make with ourselves. It is the first language we reach for. Children draw in lines before they write words. Architects build futures from lines on a blueprint. Dürer carved whole worlds out of lines in his engravings. Picasso caught the essence of a bull or a dove with a single stroke. Kandinsky wrote about lines like they were charged wires. In Japanese sumi-e, a line can hold the weight of a mountain or the sway of bamboo. The tradition is long, and every artist who picks up a pencil or brush enters into it, whether knowingly or not. Even scientists (think of Galileo’s sketches of the moon or Leonardo’s anatomy) start by tracing outlines. A line is not nature, but it is a way of approaching it. Paul Valéry once remarked: “A line is a prodigious abstraction; it is neither matter, nor air, nor shadow, yet it governs them all.” Klee called it “a dot that went for a walk.” Kandinsky charged it with force, direction, tension. Agnes Martin stretched it until it became a form of meditation. And yet, none of these artists denied Goya’s insight: that lines are fictions, necessary ones.

Today, lines extend beyond paper. They’re digital, elastic, endlessly redrawn. We scroll through timelines, swipe across storylines. Even the new words we invent — algospeak (coded slang), sharent (parents sharing children’s lives online), microdosing (creativity or wellness in fragments) — seem like contemporary lines, quick sketches of shifting cultural shapes.

Paul Ricoeur, the French philosopher, suggested that “every trace is already interpretation.” Yes, it simplifies, but also guides us toward meaning. We underestimate it because it looks so slight.

But the world is nothing if not lines: the horizon, the fold of skin at the knuckle, the telephone wires that some of us still remember as part of the landscape.

Merleau-Ponty once wrote: “Drawing is not the imitation of things, but the act by which their visibility is invented.”

Drawing is letting our hands see what our eyes cannot hold for long. And yet, as MacNeice put it, “What is beautiful is that which has no edge.” We draw in lines because they let us feel — the tilt of a shadow, the curve of what is passing, the tremor in a reflection that no camera can capture. We draw in lines to touch the spaces between forms, to mark presence without claiming control.

Every outline is a fiction; the world itself has no edge.

"A dot that went for a walk"--love that!