"Appearance rules the world"

On “The Arnolfini Portrait” and Social Status

I’ve been thinking of Friedrich Schiller’s statement lately when reflecting on the superficial nature of societal dynamics. Humans are often guided, influenced, or manipulated by influential individuals. Algorithms act as invisible stagehands, curating what we see and amplifying the voices deemed most profitable. The “influential individuals” of our time are influencers in the truest sense — digital oracles. Millions scroll, not steering their own course but surrendering to the tide of fashionable trends and viral moments.

I remember this painting precisely, from the time I didn’t know social media would exist at all. It was one of the first ones I encountered in an art magazine. I was about 12 years old. Jan van Eyck, the most famous of the 15th-century Dutch painters, portrayed a man and a woman, known as “The Arnolfini Portrait.”

The painting, housed at the National Gallery in London (painted in oils on panel), is not large, although it looked as such at the back cover of that magazine — a mere 82.2 x 60 cm. It depicts a man and a woman in a bourgeois interior, in full figures. Behind them, the silhouettes of two witnesses to the scene are reflected in a mirror, and above the mirror on the wall is the signature Johannes de eyck fuit hic / 1434 (Jan van Eyck was here / 1434). A unique feature is that the date and the artist’s signature are not on the frame, but in the very centre of the work.

Imagine an Instagram photo of a couple taken in their elegant home. These individuals present themselves in an interior filled with exclusive furniture and appliances, designed by a renowned fashion designer. They are dressed seemingly casually, and their abandoned shoes and purebred dog are by no means accidental. Through a cracked terrace window, one can see the pool and garden. They have much to boast about, and they do so without scruple, and with full awareness of what a properly constructed image means these days. And just in the middle, you discover the name of a well-known nationally-recognised photographer with an inscription … was there.

Flaunting high social standing and wealth through a carefully crafted image isn’t a modern invention. In the days before photography and social media, portraits conveyed visual status information. The more prominent the painter, the better.

Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini’s decision to commission a portrait (apparently it is not a marriage portrait, maybe at least the legal signature nomination…) from Jan van Eyck was no accident. A wealthy Italian merchant from Lucca and his unnamed partner (if that’s even who they were) posed for the most prominent artist in the Netherlands at the time — a court painter based in Bruges. Arnolfini and other wealthy burghers, lending money to kings and princes, could afford such an expense. And it was still disproportionately less than purchasing a large brass candelabra, a ceremonial bed that was the most expensive piece of furniture in the house, or a fur-lined caftan. What does a comparison of the Instagram photo with a fifteenth-century portrait painted in oils on panel reveal? The conclusion is simple, and the message is straightforward — emphasis on position.

The need for distinction has accompanied human societies since the dawn of civilisation; only the means used to achieve it have changed.

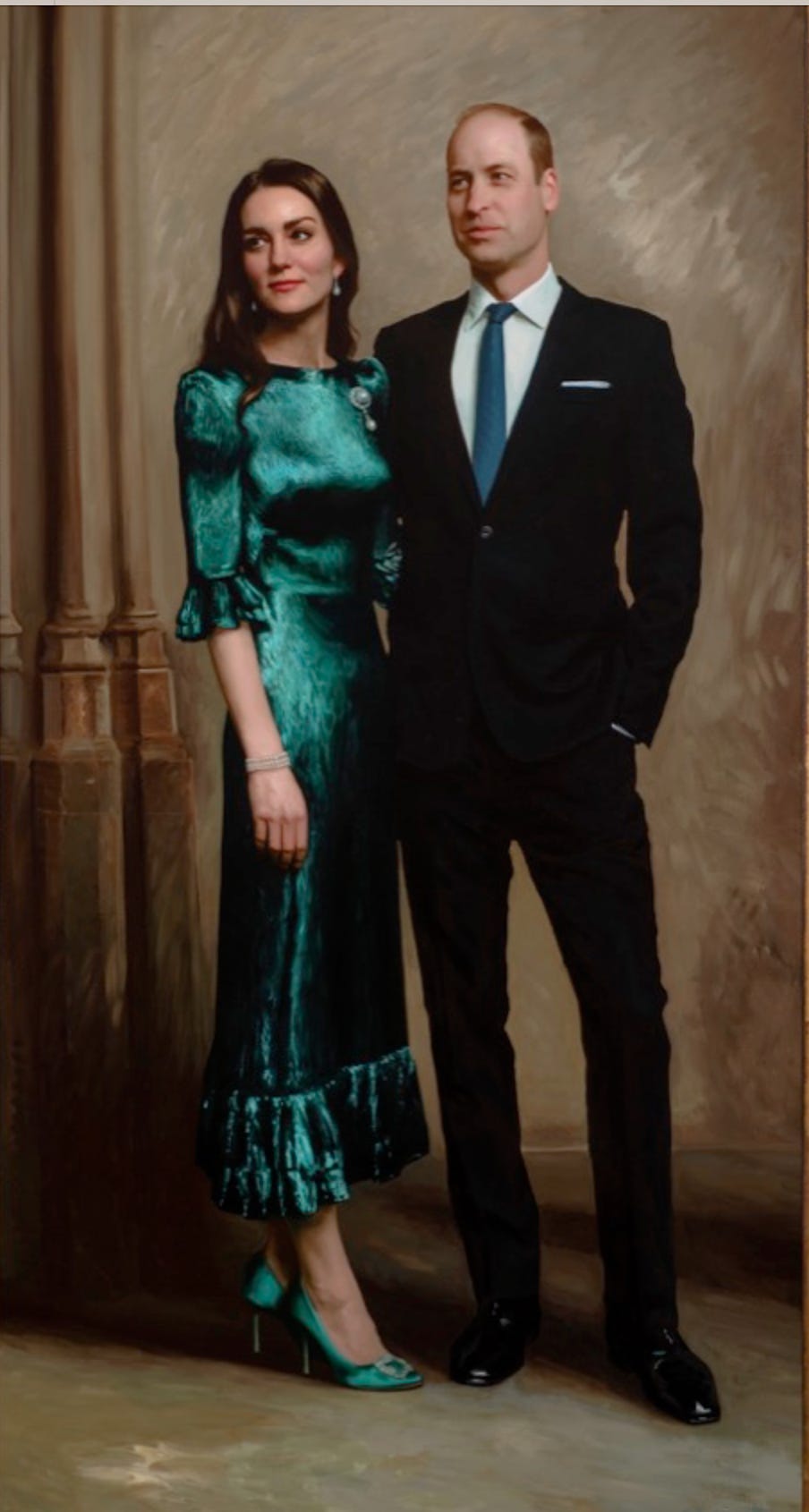

Nowadays, it’s undoubtedly easier and much cheaper to post a photograph from a prominent photographer on social media than to commission a double portrait from a renowned artist. Only a few people use the latter medium anymore, and the results can still be disappointing.

There’s another, albeit entirely coincidental, similarity between the portrait of the alleged Arnolfinis and contemporary Instagram fame. Social media isn’t just about highlighting a high profile once it’s achieved — it’s much more often about building it. A nobody can become a celebrity, and the way to achieve this is to achieve a sufficiently wide reach. The couple depicted by van Eyck is also assured fame, although their identity remains uncertain. However, they have been a part of the public imagination for years, and their portraits are even reproduced on slippers!

In the 1430s, when the portrait was painted, everyone in Bruges likely knew who the subjects were. However, over time, their identities were forgotten, and the surnames of the subjects were unknown from the mid-16th century onward. It was not until two 19th-century scholars, Joseph Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, that they pointed out that the entries in old inventories, “Hernoul le Fin” and “Arnoult Fin,” may have been a clumsy attempt to record the Italian surname Arnolfini. Expanding on this hypothesis, William Weale in 1861 identified Giovanni Arnolfini, known from Burgundian court accounts, with Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini, who died in Bruges in 1472. According to Weale, the couple portrayed would have been Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini and his wife, Giovanna Cenami.

However, modern archival research has shown that Giovanni di Arrigo, previously identified as the subject of the painting, did not marry until 1447, and the portrait — as clearly indicated by the painter’s signature placed under the mirror — was painted thirteen years earlier. Lorne Campbell, curator of London’s National Gallery, assumes that if the reading of the name “Hernoul le Fin” as “Arnolfini” is correct, then the subjects of the portraits should be Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini, who would have been around thirty years old in 1434, and his presumed second wife, as she is not mentioned in any sources.

Arnolfini’s face is very distinctive. It’s possible he was cross-eyed, and his slightly bulging eyes have prompted modern doctors to make bold hypotheses about his health.

The face of the mysterious wife lacks distinctive features, seems idealised, and resembles images of saints from religious depictions. Could this be a 15th-century Snapchat? However, the filters aren’t from any app; they were applied by the skilful hand of a talented painter. Moreover, this isn’t the only “improved” element in the painting.

The painting — both the characters’ images and the space in which they are depicted — is an evocative creation of a world in which only the details are realistically rendered. Thanks to the exquisitely rendered details and textures, the painting gives the impression of an accurate description of reality: the fur is soft, the velvets are supple, the wool is rough, the metals gleam, the floor has grain, and even the petals of the cherry blossoms blooming outside the window are visible. But why are the figures so large, there’s no room for a brass candelabra (it squeezes between the characters’ heads, yet allows every inch of it to be visible), and why are several basic elements essential to the reception interior of a wealthy bourgeois home missing? Stately beds were the furnishings of such rooms, but this one should also have included window seats and a fireplace. However, the discrepancies with reality are carefully considered and not the result of the painter’s incompetence. The reality of space is relative, and the perspective, position, and size of the figures and objects are subordinated to “marketing” purposes. From this point of view, it does not matter that the mirror is too large or the bed too small.

The painting emphasises the social roles of men and women, showing their position in the city, their piety, but also their wealth, and even their satisfaction with a prosperous, comfortable life. The oranges on the chest are not merely an attractive, colourful element in the composition or a display of the painter’s skill (they are reflected in the wood’s varnish). The exotic, expensive fruits, imported to the Netherlands from southern Europe, testify to the wealth of the owners, their ability to afford any whim. Moreover, they are not ashamed of either their merchant profession or their bourgeois origins. The painter depicts them in their entirety, as if they were rulers.

And what are the figures depicted in the painting doing? What moment in their lives is really being captured here? It was likely considered as carefully as the set of objects accompanying them.

Lorne Campbell, curator of London’s National Gallery, believes that the painting is a depiction of a scene of welcoming guests. The household members stand in a reception room, greeting the newcomers reflected in the mirror.

This effect was likely intensified when the painting emerged from behind the doors that formerly covered the painting. Opening the doors revealed a couple greeting the guests, suggesting that everyone standing before the painting was reflected in a convex mirror placed at the back of the painting. The hosts also greet the viewers standing before the painting. Thanks to the trick of the mirror, everyone — both those whose reflections actually appear in it and the viewers viewing the painting — admires the wealth of the merchant’s house and its distinguished hosts.

The master of the house greets the guests with a gesture, extending a friendly invitation. He is dressed in a fur-lined tabard, despite the spring day; he has displayed oranges, exotic in the north. The painter has enlarged the faces of the characters and their precious objects, including the convex mirror, so that they are clearly visible. The wish of wealthy merchants to immortalise their earthly success and position was enriched by van Eyck with a painterly trick, a game with the viewer so intriguing that it was repeated by other great painters, for example, Diego Velázquez in Las Meninas.

Inside the painting, there’s a clear message — the painter’s signature and an invitation for the viewer to follow in his footsteps, to examine and admire the exquisite house. This isn’t a complicated puzzle, as has been assumed for decades. Viewers aren’t invited to decipher the painting’s intricate meaning, but to observe the Bruges home, the wealth and hospitality of its inhabitants, while simultaneously admiring the artistry of the painter’s refined performance. Doesn’t everything seem real, even though it isn’t? Standing before the painting or looking at it printed in an art magazine or published online, don’t we feel as if we were standing on the threshold of a house, seeing our reflection looming in the mirror?

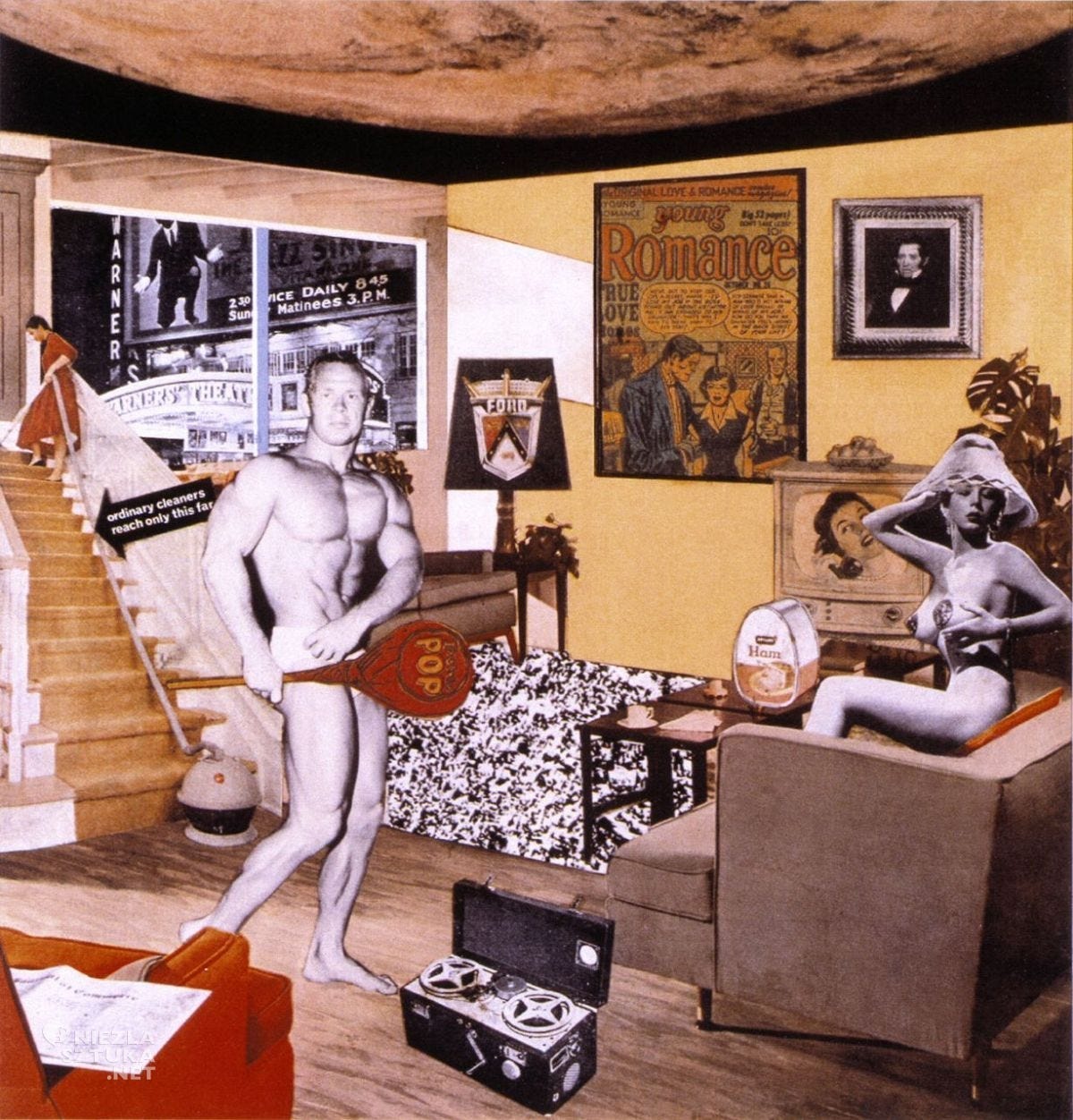

The Arnolfini Portrait is also a source of inspiration for contemporary artists, representing the beauty ideals of their time. For example Hamilton’s subjects are depicted in their own homes and surrounded by desirable objects.

In the painting “Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy,” Hockney draws in various ways on the traditions of the Old Masters. The genre itself — a double portrait of a married couple in an interior — dates back to the 15th century and establishes a subtle dialogue with van Eyck’s painting. However, Hockney’s subjects do not hold hands; a chill reigns not only in the minimalist and fashionably furnished interior but also between Ossie and Celia Clark.

If Eyck’s couple belonged to Instagram, Hockney’s to the official painting hung in a museum, and Jamie Coreth’s to the kind of portrait that might rest cosily on a living-room wall, how would you wish your own union to be portrayed?