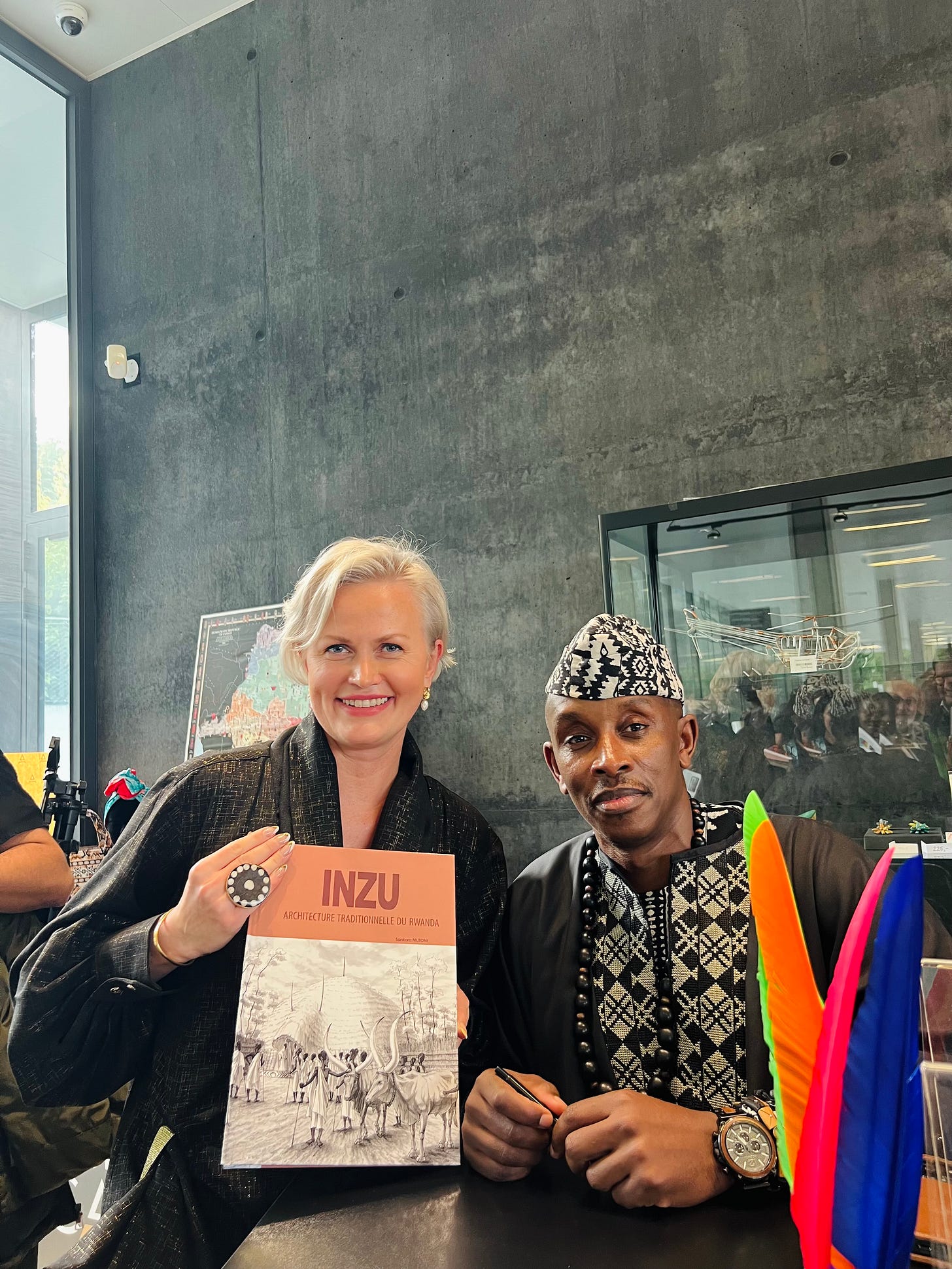

Muraho, bonjour, hello. I’m very pleased to be here with SANKARA MUTONI, an artist born in Rwanda, who works in Belgium, an architect and the author of this new book called… Inzu.

Inzu.

That means the house.

The house in Kinyarwanda.

We’re going to talk about the culture connected to the house — to our enclosures, to what is closest to us. Thank you for being here to share in this conversation. First, why don’t we still build a circle? Why aren’t we still in that space where there was family, the circle of friends, in fact, the community?

In fact, because originally, constructions in Rwanda were linked to a family lineage, meaning that people lived within a lineage. For example, you could live on a hill and find, for instance, the head of the family with his first wife, his second wife, of course with their children, and then you would find the married sons who did not yet have the means to build their own house. And so the word Inzu means house, but Urugo was originally a word that referred precisely to all these constructions that were placed within enclosures, and these enclosures were connected to each other.

That’s what was called Urugo. Indeed, in the current state, because Rwandan families have changed, we are mostly dealing with families, I would say, meaning father and mother, mostly monogamous families. But indeed, those constructions which were for extended families also included polygamous families.

That’s why maybe they make less sense now because people’s lifestyles have changed. So the construction has adapted. But yes, that’s mainly what has changed in the current construction of Rwanda.

I’m deeply drawn to the aesthetics of the past — and, like you, I find a unique beauty in Rwandan architecture, particularly in its attention to detail. Could you tell us more about the traditional finishing techniques and what makes them distinctive?

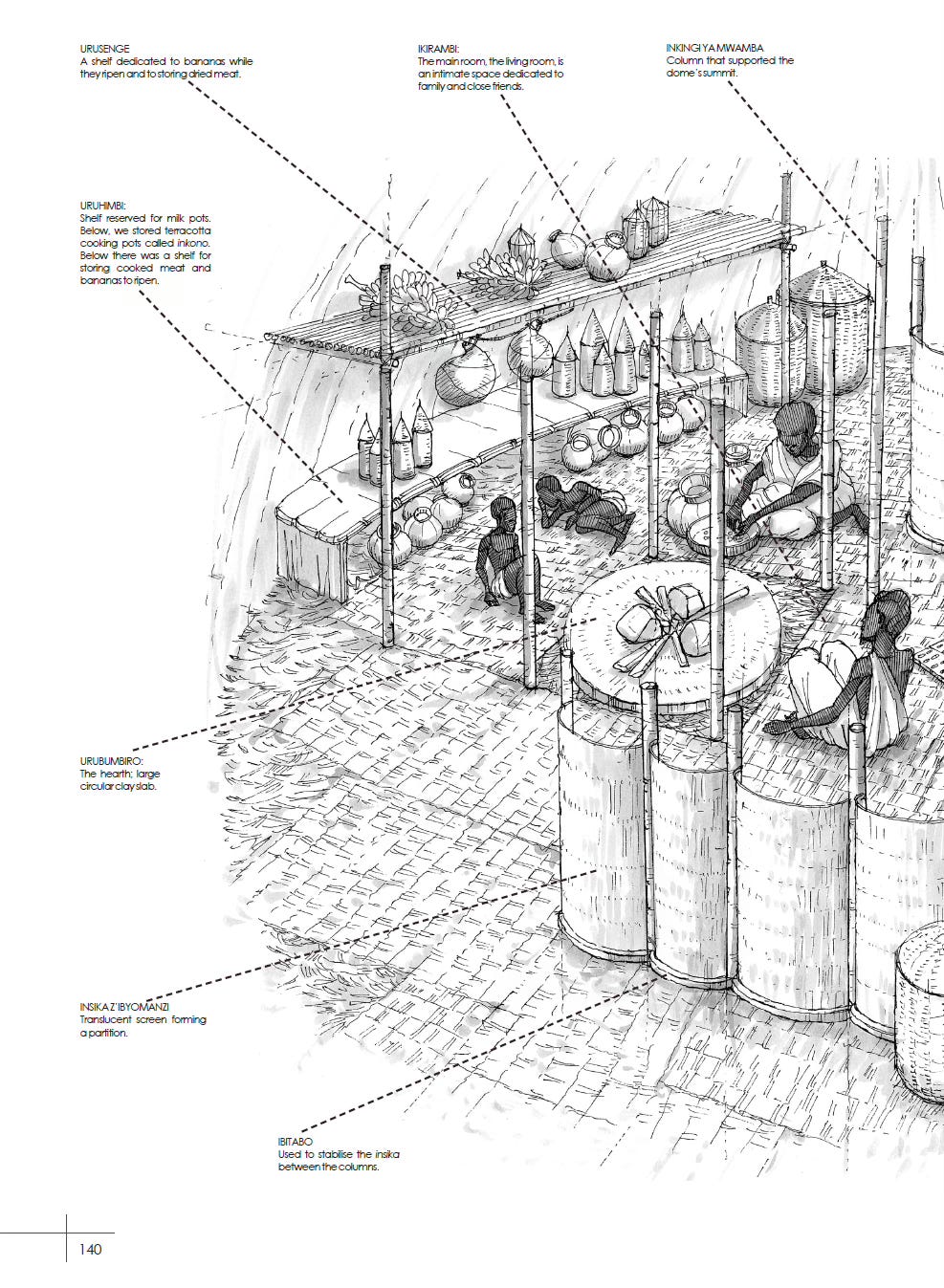

The details of the construction. Indeed, all these houses were built… it was almost like wickerwork. In fact, they called a construction “wickerwork” (architectural basketry, practised only by men, used in the construction of houses, grain granaries, and fences). It was a wooden structure on which horizontal elements were woven.

So, all the vertical wood was placed like an inverted basket, and the ends were joined to form the dome, and then everything around was woven with wood fibres, so it was ropes with flexible wood. And on that, a basket structure was created, and these basket structures were then covered with dry grass, which we called ISHINGE, and inside, we would weave again, like in a basket. It was completely woven.

So, for those who had the chance to visit the King's Palace in Rwanda, you can see it. So, it’s completely woven.

We could say it was an ancient wallpaper.

Yes, exactly. It’s like an ancient wallpaper, except it was handmade, completely woven.

And to make partitions inside, we also used removable partitions in wickerwork, which were fitted into semicircular elements made of baked clay, which we call IGITABO in Kinyarwanda.

IGITABO, because IGITABO means to bury — earthen.

IGITABO K’INKOMANE — A threshold served to protect the interior from water runoff and to the privacy of the occupants. INKINGIYA YA KANAGAZI — column supporting the part of the roof covering the entrance of the house. They marked the separation between the inside and the outside of the house.

Interestingly, the word IGITABO also means book. That’s it.

That’s fascinating. Is it why you decided to annotate the book with the original terms?

Precisely, it was important to preserve the words, because you could also find a finesse in the words. Contextualising words was also very important. So here, in the book, I included all the descriptions of constructions in Kinyarwanda. That’s how I myself personally learned all these words.

Some I knew, others I didn’t. I knew the word IGITABO, but IGITABO, which means this semicircular element that serves as a threshold to enter the house, which also serves as the semicircular element to hold the partitions—I didn’t know it was called that.

But that’s why I said the words were very important to update, because with the words, we understand better. I’m talking about the words here in Kinyarwanda. With these words in Kinyarwanda, we understood better the architecture of that time, because it’s actually difficult to analyse it if we’re not also trying to understand the original words, the words people used to describe what they built. Indeed, all this basketry is truly beautiful. I think Rwanda was remarkably sophisticated — perhaps because it was a centralised and stable state for several centuries, which gave people time to refine their techniques. And so, all these magnificent partitions, which obviously make Rwanda shine, but not only, all the woven baskets, etc. For example, here, all this wickerwork, in a period photo, you can see them woven; they all had completely different patterns.

And what you can also notice is that they had a great variety in shapes as well. That is, in terms of uniformity of patterns. You should also know that in ancient Rwanda, each pattern had its name. Here, we see them in the reconstruction of the King's Palace in Nyanza.

Of course, there were two types of partitions. There were completely opaque partitions through which one could not see. Partitions in Kinyarwanda are called Insika. And then there were those through which you could see a little bit. And so, inside, we could see what was happening outside, but people outside could not see us.

And those were called Insika Zibiomanzi. But those were mainly placed at the entrance. And the ones that were more densely woven, completely opaque, were placed in the living room. But obviously, this was very expensive work, often found in wealthy families and, of course, with the king.

But for example, here, there was a fireplace inside. So it was a huge clay slab, molded in place.

It’s original, it was like that?

It was like that. This is the reconstruction, of course, of the King’s Palace in Nyanza, where we see all these magnificent woven partitions, woven with natural materials. And this is the living room of the king’s house. Here, we see the chair on which he sat when he had guests.

This is an entrance, actually, to go… to his bed. And in the centre, in this living room, there was a huge clay fireplace, called IBUMBA, as we say in Kinyarwanda, and on it was placed, basically, a pot, if you like, made of iron, in which firewood was burned to provide lighting inside.

Also, inside, sometimes cow dung balls were placed. You should know that cow dung, when burned, produces smoke that keeps insects out. So it’s a natural insecticide. That’s what it was used for. Obviously, in the king’s house, this slab wasn’t used for cooking. We didn’t prepare food on it because the king had a kitchen in another house inside his urugo. So for the king, it was just a decorative or ornamental fire to light the rooms and also, as I said, for burning cow dung mixed with charcoal to prevent insects inside.

So it’s a natural insecticide.

Please tell us a bit about how the book was born…

Yes. So, this book, which is called Inzu, was born out of a desire to explain Rwandan architecture, that is, of my native country, but through a cultural and religious lens. Because for me, these constructions were part of a whole. This connection was essential to make sense of it all—to avoid seeing these as isolated objects without a foundation, as objects we come to see in a museum, to admire or to denigrate, but rather to show that all of these forms are part of a greater whole. What interested me first was to understand the paradigm—the way of thinking. The mindset of the people who counted, who lived at that time, who built those houses: what were their thoughts, their ideas, their vision of the world? That’s what intrigued me, and that’s the angle from which I approached this book.

In the book, I begin with history. I talk about Rwanda’s economic system at the time—before colonisation, there was already a religious system centred around ancestor worship, and of course, around the culture of the cow, which was truly the central element. Cows were part of governance; they had monetary value—they were literally the country’s currency.

By understanding these two elements, I was able to analyse the architecture in depth. The most important thing was to create links between ancestor worship, the cow-based cultural system, and the built environment. It was crucial to build that foundation, to anchor these objects in a story, in a territory, and in a worldview.

And that’s where I think it all begins—with KONDO. Isn’t that right? Kondo, gakondo—heritage, tradition. The concept is that everything was created by God, who has a will for humankind… What I found fascinating is that clay, or IBUMBA in Kinyarwanda, and KONDO in Swahili, both come from that same root idea—earth, clay, dust. When we sing or play music, we return to what God created us from: the earth. That’s the recurring idea—that architecture, materials, and creation all come from the soil.

Exactly. It’s the realisation that everything is interconnected. God, the earth, the elements, and human beings form one whole that gives rise to architecture. That’s what I explore in this book: the belief in Imana—God—the nurturing earth that gives us everything, from trees to building materials, and the humans who shape them. The relationship between the two was central, which is why the world of spirits—through ancestor worship—was so important in that society.

Ancestor worship formed the link between the earth and Imana, since people believed we were the children of Imana. Death was not the end—our spirits continued to live.

As you mentioned during the guided tour, there is the body and then there is the spirit that continues to live. That’s why people believed their ancestors had not truly left—they were still there to guide, support, and tell stories.

Yes.

And there were also specific places devoted to that worship.

In traditional Rwandan homes, there was a courtyard, a back courtyard, and the house at the centre. The sacred objects or altars were usually placed in the back courtyard. For those who had no back courtyard, they would place them in front. These were small chapels where people would make vows or seek guidance from their ancestors. If an ancestor had died in painful circumstances, one might pray for their soul to find peace.

People also prayed for guidance—saying, for example, “Grandfather, beloved ancestor, please help me succeed in this project.” These were common forms of prayer. Ancestor worship went further still, involving diviners, because the relationship between Imana (God) and humans was not direct. There had to be intermediaries—diviners, kings, or spiritual figures. One of the best-known cults in Rwanda was that of Ryangombe, a figure to whom people paid homage.

The story goes that Ryangombe, while hunting an antelope, shot an arrow thinking the animal was dead. But as he approached, the antelope suddenly rose and threw him into a tree with its horns. He died there, and that tree became sacred—a tree of good fortune. That is why, even today, trees are planted at the entrances of compounds—to recall that story.

This shows the deep connection between Imana, humans, and the earth—manifested in architecture that was alive, made of trees, living matter. The same trees were used to build, to make fire, to care for the cows.

It all formed one cycle—nothing was created or lost, everything transformed.

As Lavoisier said, “Nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed.”

That’s exactly the philosophy behind ancestor worship: the belief that when a person dies, their body decomposes, is eaten by worms, which are then eaten by birds, which are eaten by cats, and so on—the cycle continues, but the soul endures.

And this makes sense—it is, in a way, scientific. That was the ancient belief.

Now, let us present the book.

Here’s the book—it’s richly illustrated, with historical images and many of my own reconstructions. For example, here are plans of traditional Rwandan compounds, showing the passageways for cattle, the stages of construction, different building methods, and views of the interior.

Anna, thank you very much for this interview. See you very soon.

Thank you for the opportunity to talk about it. It’s been wonderful.

SOME EXTRAS:

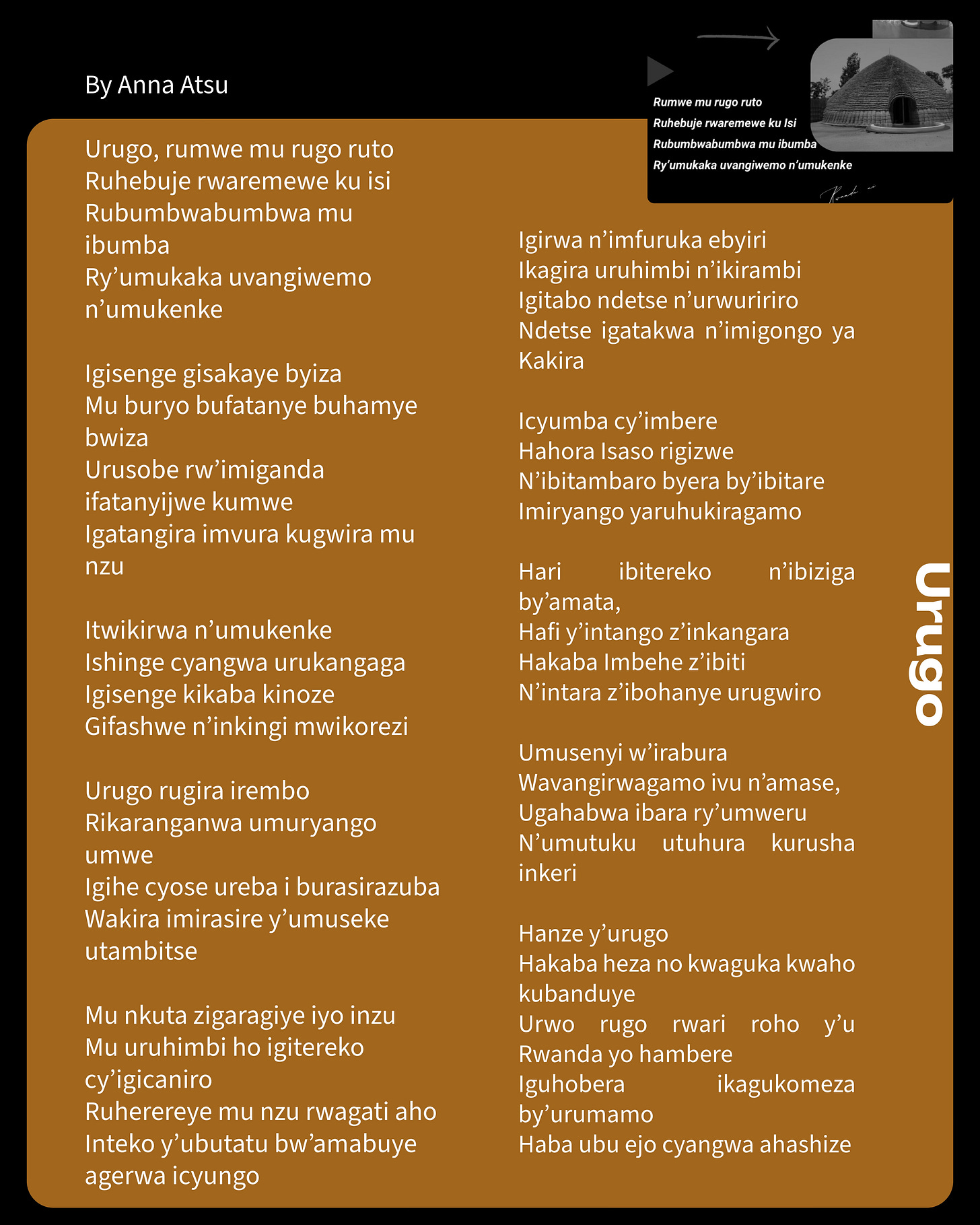

My poem, entitled URUGO

Watch the video:

Read it in Kinyarwanda:

Previous interview with SANKARA MUTONI about his life and artistry:

CLICK THE LINK:

Rediscovering Roots Through Art: A Conversation with SANKARA MUTONI