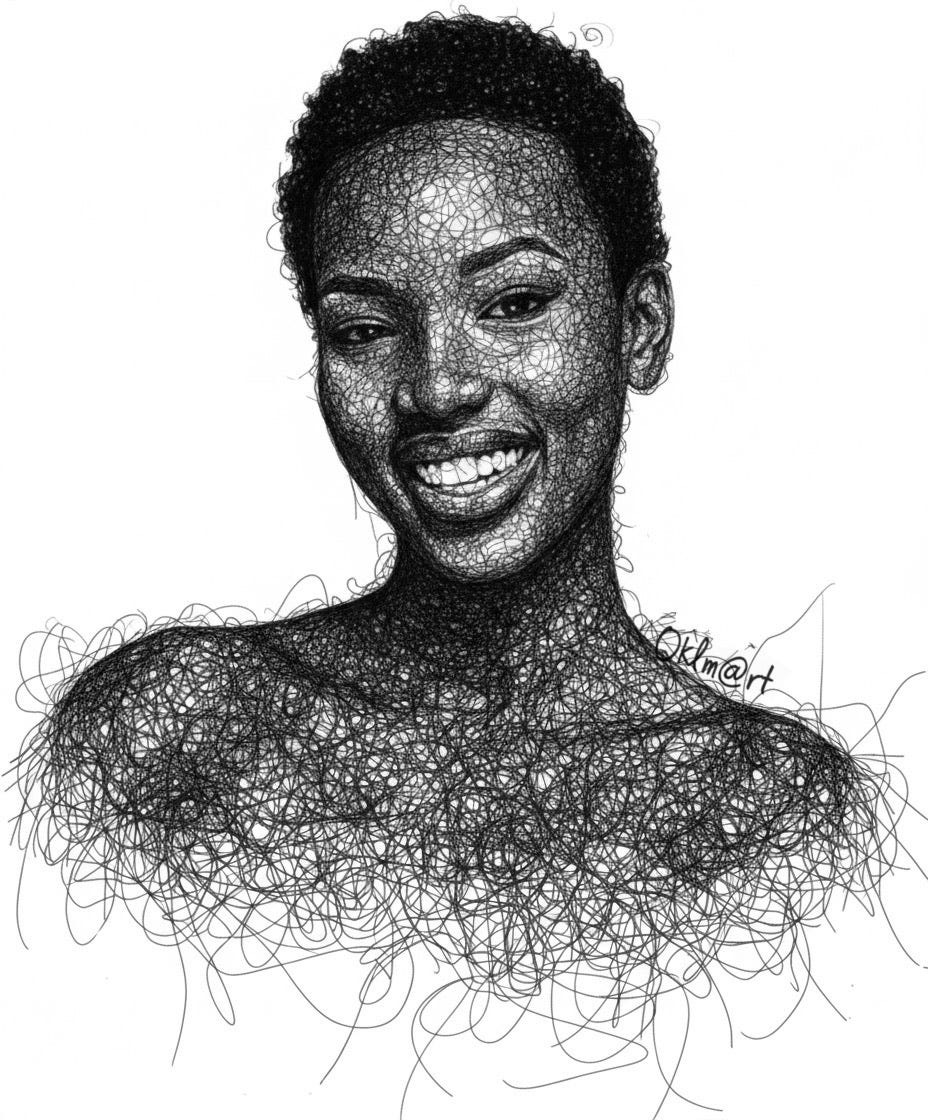

In Burundi, you say “Agaceceka karavuga” — silence speaks. When we look at your drawings — a thousand lines for a single look — what are we stepping into?

To some, ink might appear chaotic, but when we look, look closely, a soul stares back at us. There is a threshold there: between what we see and what we feel. I invite people to enter that space. In my drawings, nothing is accidental. Even the pauses matter.

Please, introduce yourself.

My name is Selemani CHERUBALA Philippe-Dan, but the public knows me as OKLM. I am a multifaceted artist, a musician and a visual director.

My identity and creativity feed on my roots, proudly anchored between two pillars of Africa: DR Congo and Burundi.

I define my work as a mixture of authenticity and modernity.

My goal is simple: to use my director’s eye and my musician’s ear to offer a complete and unique artistic universe.

Your piece IREMBO feels both dense and calm. Please tell us more.

IREMBO means beauty, but not the loud kind. It’s the beauty that settles after struggle. The kind that remains when the noise is gone. It is about someone who no longer searches for his place in the world, but for peace within himself.

Your work feels deeply rooted. Tell us more about the soil you grew from.

I was born into a large family — I’m the seventh child. My childhood was rocked by combat sports, but even more by music. I started singing at four years old, in a Catholic choir. I inherited that love from my mother; she was a singer and a youth leader when she was young.

Our house was always full of things: music, fighting sports, drawing, pastry… creation in many forms.

I discovered drawing through manga, and through my older brothers, who were already drawing a lot.

My family gave us a principle to follow:

If you want to do good things, start with the small ones — and do them well.

Remain authentic.

Put God at the centre of everything, even your talents.

And above all — do what you love, and truly do it.

In Burundi, there’s a saying: “Ukurusha abandi si uwiruka cane, ni uwamenye iyo aja.” The one who goes far is not the one who runs fastest, but the one who knows where he is going.

That stayed with me.

How did it begin with art? What difficulties did you encounter, and what arts bring you as a state of mind?

I can’t say that I encountered art; I can say that art chose me. As I mentioned before, I was born into a large family where everyone had their own talent or particular gift, but music was something that truly belonged to us. I discovered it at the age of five, and I have continued to practise it up to this day.

As for drawing, I can say that I discovered it and that it, too, chose me. By watching manga with my older brothers and seeing them reproduce certain characters, I began to wonder how they managed to do that... It was from that point that I also started drawing, and that’s when I realised I had a particular talent in that world as well.

Of course, it wasn’t easy —

especially in the society I grew up in, a society that saw art as a waste of time, a society that did nothing but talk and criticise…

But fortunately, it’s thanks to that very society that I developed the mental strength and mindset I have today.

Art, for me, is a second nature, a second home, a life.

It’s something that allows me to express myself, to express things I maybe couldn’t express verbally or directly. I would say that art came into my life to show me who I really was and why I loved art so deeply.

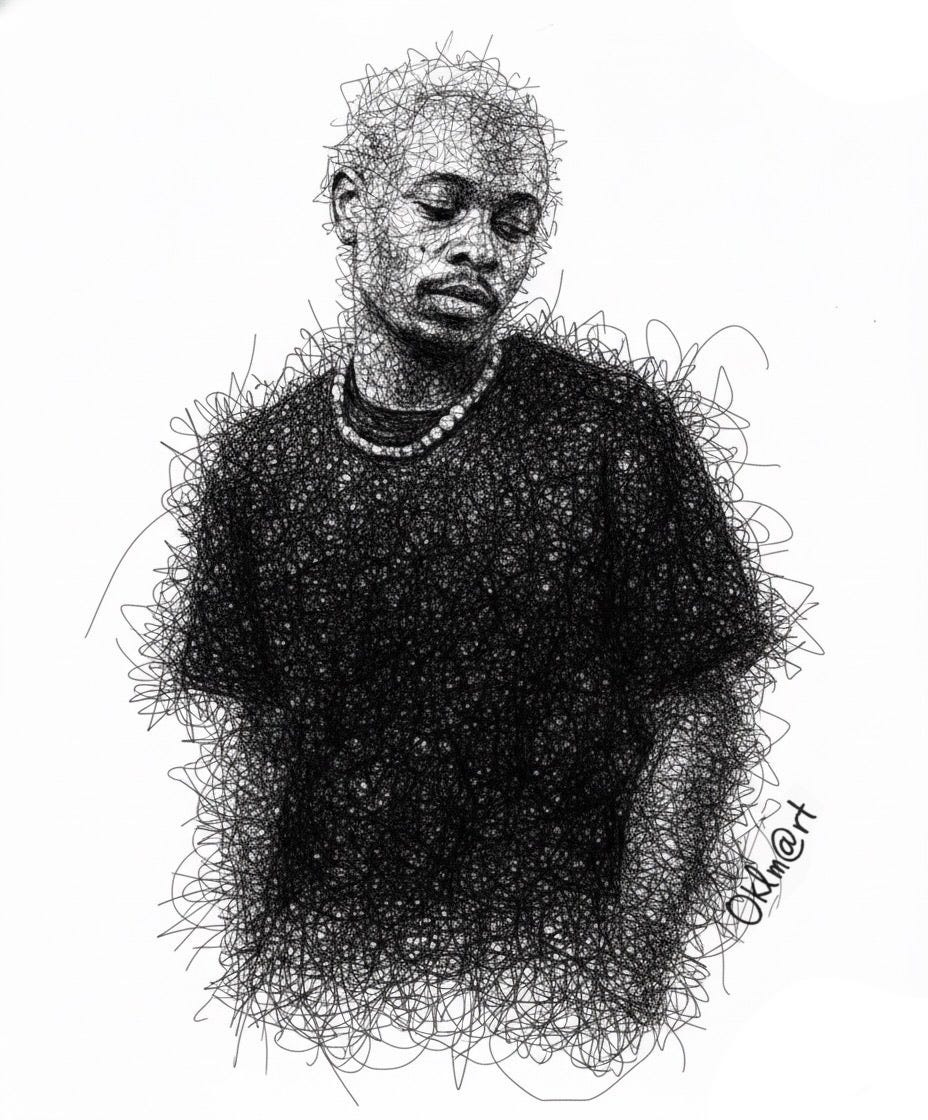

One of your most striking works, INGABO, radiates strength.

Here, force is silent, dignified, indomitable. He is the son of the hills. He is the rock of the country. INGABO means shield. Not the kind you swing, but the kind you become.

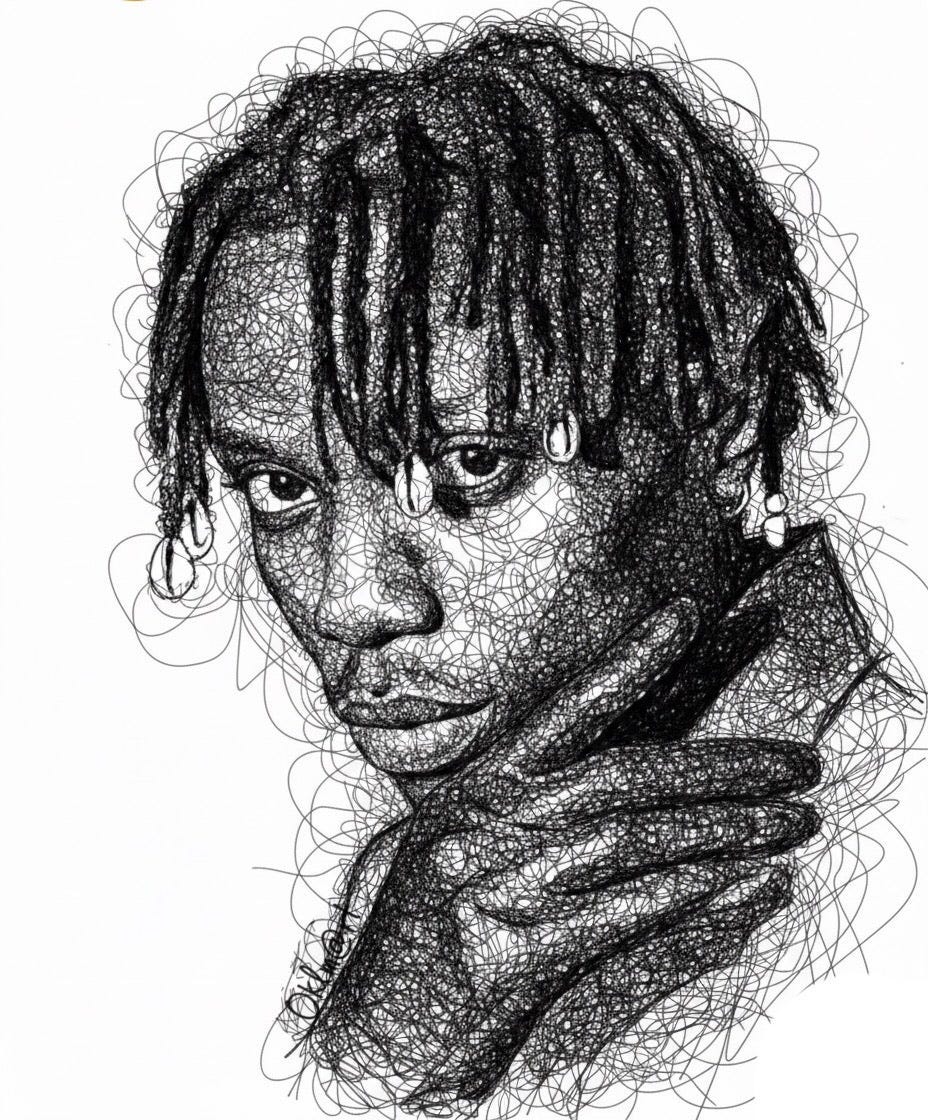

The piece MUKULU feels intensely personal.

It is my Inkingi — my pillar. The eldest. The one who opened the road so that I wouldn’t stumble. He wasn’t only a big brother; he was my shield and my first support. Mukulu — the eldest — is blood, foundation. The one who gave everything so I could stand upright.

This portrait is my debt of recognition. In Kirundi, we say:

“Uwutagukingiye mu mvura ntazokubakira izuba.”

The one who didn’t shelter you from the rain won’t build you a house in the sun.

He sheltered me.

Your lines feel almost obsessive — dense, layered. Why this intensity?

Because memory is never clean. Life doesn’t arrive in straight strokes.

I don’t rush faces. I let them tell me when they are ready.

When someone stands before your work, what do you hope they carry with them when they leave?

Stillness.

If they feel seen — even briefly — then the passage has worked.

Because sometimes a single look, patiently drawn, can hold a thousand lives.

Thank you for today’s conversation. We wish you all the best in your life and your career.

To learn more about Dan and his art, please check his profile.